US-based researchers have successfully kept alive the brain cells of decapitated pigs for 36 hours, sparking concerns over the ethics involved in such frontline research.

The MIT Technology Review said a team at Yale University led by neuro-scientist Nenad Sestan had carried out experiments on between 100 and 200 pigs sourced from an abattoir.

Sestan had presented the findings of the experiments, where his team restored blood supply to the dead pigs’ brains, in late March to a conference organised by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

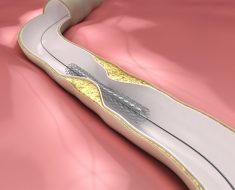

The researchers said they had succeeded in delivering oxygen to the cells via a system of pumps and blood maintained at body temperature, the MIT Technology Review said.

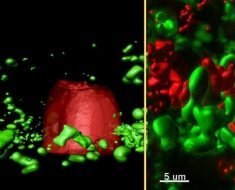

Thanks to this system, dubbed BrainEx, millions of cells were kept in good health and were capable of functioning normally, the review said.

However, there was nothing to indicate that these cells experienced some form of consciousness, it said, citing Sestan as saying he was “convinced” they did not.

Such experiments could herald advances in restoring blood circulation at the micro level, including in the brain, the article said.

They could also be potentially useful in the study and treatment of some cancers and debilitating diseases such as Alzheimer’s, it added.

At the same time, the article noted that Sestan himself raised some of the ethical issues involved in such research.

The key question being that if a brain is revived in this way, would a human being involved have any memories, an identity and rights?

In an open letter publised Wednesday in Nature magazine, Sestan and another 16 top scientists and philosophers said the authorities should lay down specific rules to guide them in their work on human brains.

Recent advances have seen what are known as brain “surrogates” composed of real human cells—whether in tiny organoids grown in the lab, in grey matter removed from a human patient, or brain tissue implanted into animals—as part of efforts to study the brain.

The risk is that “as brain surrogates become larger and more sophisticated, the possibility of them having capabilities akin to human sentience might become less remote,” the Nature article said.

“Such capacities could include being able to feel (to some degree) pleasure, pain or distress; being able to store and retrieve memories; or perhaps even having some perception of agency or awareness of self.”

Source: Read Full Article