A short video describing the potential benefits and risks of low-dose CT screening for lung cancer in addition to an informational brochure increased patients’ knowledge and reduced conflicted feelings about whether to undergo the scan more than the informational brochure alone, according to a randomized, controlled trial published online in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

In “Impact of a Lung Cancer Screening Information Film on Informed Decision-Making: A Randomized Trial,” Sam M. Janes, MBBS, Ph.D., and co-authors report on a study of 229 participants at a London hospital who met any of three criteria used to select patients who may benefit from the screening. One criterion was the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommendation of a 30 or more pack-year smoking history in patients who quit less than 15 years ago.

The authors note that studies show that fewer than 2 percent of the 7.6 million former smokers in the U.S. who are eligible for the screening actually undergo the CT scan, despite the fact that it has been shown to reduce lung cancer mortality by 20 percent.

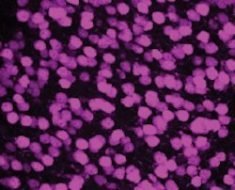

The most significant potential harms from screening come from detecting nodules, or small masses of tissue, that are usually benign but cause anxiety and may require additional scans or biopsies to determine if they are cancerous or not.

Dr. Janes, senior author and head of the Respiratory Research Department at University College London and director of London’s Lung Cancer Board, said the goal of the video was to produce a tool that would help facilitate a conversation between patients and their physicians and lead to shared decision-making—a requirement for Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement in the U.S.

“We used feedback from other patients eligible for lung cancer screening to create a film that individuals from a variety of educational backgrounds could understand and that presented the information in a clear, simple and palatable manner,” he added.

The researchers used a questionnaire to measure participants’ knowledge before and after reading the 10-page brochure or reading the brochure and watching the five-and-a-half-minute video. The researchers also measured the level of conflict the participants experienced in deciding whether to be screened or not.

At enrollment, participants answered 5 of 10 questions correctly on average. After reading the brochure, participants in that arm of the study answered seven questions correctly. After reading the brochure and watching the video, those in that arm of the study answered eight questions correctly.

Those who read the brochure and watched the video were more likely to answer two questions correctly compared to those who read only the brochure. The first question focused on the fact that uncertainty about whether a pulmonary nodule found on the scan is cancerous or not does not mean that there is a high risk of cancer. The second question focused on the fact that the amount of radiation produced by a single scan is about the equivalent of a year’s background radiation.

Members of both groups were just as likely to undergo the scan, with more than three in four choosing to be screened. However, those who watched the video as well as read the booklet were more certain of their decision to either have the scan done or not. On a scale of zero to nine, their level of certainty was 8.5, compared to 8.2 among those who only read the book.

Study limitations include the fact that all participants were enrolled in a larger lung cancer study, and half of them would have seen the informational booklet before participating in the study reported in Annals ATS.

Source: Read Full Article