Scientists have long tried to understand how pathogenic bacteria like Helicobacter pylori, a risk factor for stomach ulcers and cancer, survive in the harsh environment of the stomach. In a new study publishing May 2 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, researchers led by Connie Fung and Manuel Amieva at Stanford University propose that H. pylori exploit a specialized niche that provides safe harbor deep in the gastric glands to maintain lifelong colonization.

It was already known, from work by the Amieva Lab and others, that H. pylori colonies attached to epithelial cells deep in the gastric glands. This location, the researchers hypothesized, might protect these bacterial colonies from the constant turnover of bacteria at the stomach surface, allowing them to serve as stable bacterial reservoirs.

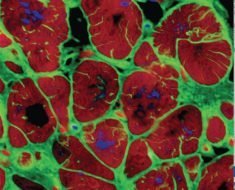

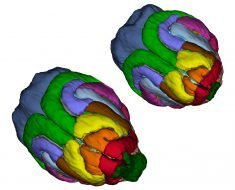

To determine how H. pylori establish, spread, and persist within the gastric glands, the researchers used high-resolution imaging and mapping techniques to visualize these gland-associated populations in animals colonized with a mixture of H. pylori marked by different fluorescent colors. The infected stomachs were processed using a technique called passive CLARITY, which renders tissues transparent. This allows for intact organs to be imaged in their entirety. The authors discovered that a small number of bacteria act as “founders” that establish within individual gastric glands, replicate, and form colonies. Subsequently, the bacteria spread locally to adjacent glands, forming large clonal population “islands” of the same color that founded the initial gland colony. These population islands persist over time and prevent any incoming bacteria from establishing in the gland space. Consistent with this observation, H. pylori mutant strains that cannot colonize the glands are outcompeted by wild-type bacteria.

These results suggest that a specialized niche in the gastric glands houses a stable H. pylori reservoir that supports chronic infection and may replenish the more transient bacterial populations in the surface mucosa. Similar to their findings with the gastric glands, other groups have also shown that commensal bacteria reside within the intestinal crypts, suggesting that these deeper sites within the gastrointestinal tract may be critical niches for microbial persistence.

Source: Read Full Article