For most types of cancer, the primary tumor is not the cause of death, but metastasis, the dissemination of cancer cells throughout the body. Metastatic progression is a complex cascade of steps, and there can be a significant delay between the initial spread and subsequent growth, eventually destroying vital organs, such as the lung, liver or brain.

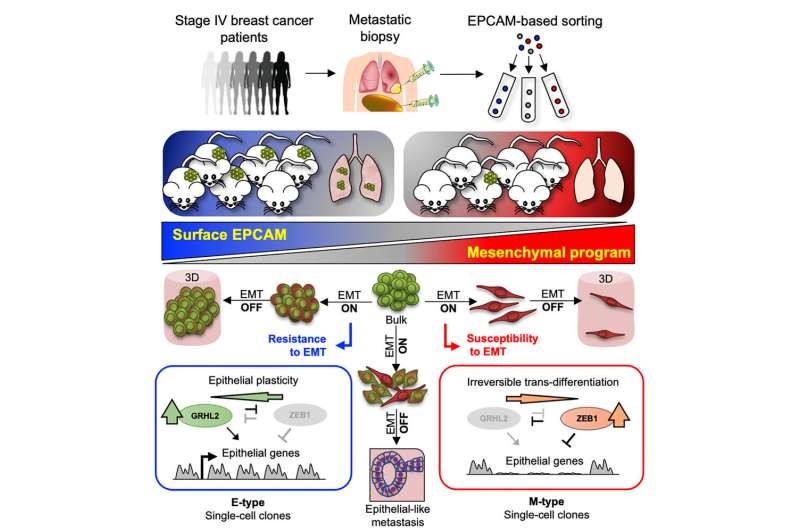

Researchers from the Skin Cancer Center at Ruhr University Bochum, the Helmholtz Center Munich, the German Cancer Center Heidelberg and the ETH Zurich have studied the properties of metastatic breast cancer cells by directly analyzing metastatic biopsies from patients.

Their new paper, published in Cell Reports, presents new mechanistic insights into how the most aggressive cancer cells proliferate and propagate the disease.

Cells change their identity

They initially focused on the activation of a cellular program that has long been implicated in metastasis, the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). In experimental settings, the activation of this program has been shown to change the identity of cancer cells, such as breast or certain types of skin cancer, thereby rendering these epithelial cancer cells more motile through the adoption of properties of mesenchymal cells, such as fibroblasts.

Importantly, the researchers discovered that both epithelial and mesenchymal cancer cells were present in metastatic biopsies. However, only the epithelial cells propagated the disease and initiated new metastases in experimental models.

“There are still conflicting data on the exact role of EMT in metastasis” said Dr. Christina Scheel, one of the senior authors. “We think our discovery has the potential to unify many of them by describing a new mechanism at play.”

Specifically, the researchers then employed a series of molecular analyses to discover a global epigenetic program in breast cancer cells that determined whether these cells were able to hold on to their epithelial identity upon activation of EMT or become completely reprogrammed to a mesenchymal cell state.

The latter process was associated with lack of growth potential. Finally, the authors describe that the interplay between two proteins, the transcription factors ZEB1 and GRHL2 determined which route breast cancer cells take upon activation of EMT. Thereby, this work reveals at the molecular level how cancer cells employ plasticity, the ability to change fundamental properties, to adopt properties that promote metastatic growth.

In the future, it will be highly interesting to determine to which extent these observations can be transferred to other epithelial cancers and also, whether these insights can be used to therapeutically target the most aggressive cancer cells.

More information:

Massimo Saini et al, Resistance to mesenchymal reprogramming sustains clonal propagation in metastatic breast cancer, Cell Reports (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112533

Journal information:

Cell Reports

Source: Read Full Article