Talking points

- ACL reconstructions in people aged 16 and older tripled in the 10 years to 2013, Medicare found.

- 15,000 primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) knee reconstructions are done annually in Australia.

- The global ligament and tendon repair market estimated at $10b annually.

The long, strong and tough tendons of a kangaroo could be the key to getting athletes like injury-plagued Sydney Swan Alex Johnson back to full health, according to a Bowral orthopaedic surgeon.

The Swans defender, in his second game back against the Melbourne Demons after six years out with injury, damaged his anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) on Sunday, and could require his sixth knee reconstruction.

Agony: Alex Johnson is helped off the field with an ACL injury.

Currently to repair an ACL, a surgeon may use a hamstring. If it is ruptured again, they make take a hamstring from the other leg, or a patella tendon, causing additional recovering time. Tissue from a friend or a donor is often rejected, while material from a cadaver may be from someone much older than the player.

Replay

But with kangaroo tendons as much as six times stronger than the human ACL, researchers hope that using this previously unwanted byproduct from a kangaroos' rear legs or tails could put the spring back in an athlete's step (or knees).

A mob of grey kangaroos on the run through Oxley Station in Macquarie Marshes in the Western Plains of New South Wales.

Following testing this year by Bowral orthopaedic surgeon Dr Nick Hartnell, The University of Sydney has partnered with his company and two others to provide $2.4 million for pre-clinical trials. They'll examine the efficacy of kangaroo tendons in knee, ankle and shoulder ligament replacement.

"If you ever want to know why we need roos, we need them for poor guys like Alex. He's run out of options," said Dr Hartnell, who operates regularly on athletes with injured knees. "All the (existing) options are very bad if you are trying to get back to AFL," he said.

Sydney University's Dr Elizabeth Clarke said the pilot test found that the strongest kangaroo tendon from a kangaroo tail or leg was six times stronger than a human.

The macropod's tendons were structurally similar to a human tendon but stronger and longer, and even the weakest roo tendon was two to three times stronger, found Dr Clarke, an expert in injury biomechanics, and leader of the kangaroo tendon-testing project.

Researchers in the USA have been given approval to use tendons from pigs, but these tendons are very short.

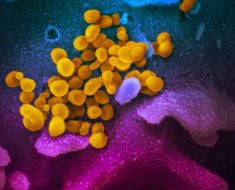

Dr Hartnell says human hamstring tendon (shown here in knee reconstruction surgery) is remarkably similar to a kangaroo’s, although a roo tendon is as much as six times stronger.

"What you want is something that's reproducible, off the shelf and not compromising post-operative rehabilitation," said Dr Hartnell. He estimates that at least 10 per cent of his work is repairing ruptured ACLs with another 50 per cent reconstructing knees later in life.

"That's why I came up with the idea of kangaroo tendon. I just got sick of pulling out hamstrings in young kids," he said.

When a 13-year-old friend of his daughter hurt her knee skiing, he promised her he'd do something – prompting him to fund the initial tests.

"The marketing is easy: People are always asking me to put some bounce back in their step," said Dr Hartnell. He was inspired by watching kangaroos near his home in Bowral, and realising that the tails and the legs were thrown out as waste to the "crows".

Kangaroo tendons are six times stronger than human cruciate ligaments.

The next stage was looking at whether the process of making the tendons safe for transfer to a human (by removing the cells and sterilising them) would weaken the tissues. But Dr Clarke said they were hoping "that we will end up with something stronger than what's on the market today".

Because kangaroos can hop as far as four metres at a time, the musculature of their back legs including tendons was incredibly well developed, said Dr Mark Eldridge, principal research scientist with the Australian Museum. They were so tough and strong, they were used as chewy treats for dogs, he said.

The Sydney University trial will also test a new synthetic material, strontium-hardystonite-Gahnite (Sr-HT-Gahnite) which dissolves as the bone grows, to screw the tendon to the bone.

Source: Read Full Article