During the last few months of her pregnancy, Lisa Livesay closed the door to the nursery she and her husband, Chris, had created for their third child. She couldn’t bear to look inside, not knowing if the cozy space would ever be home to their baby.

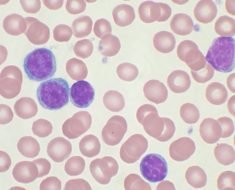

The couple had anticipated their usual complications—Lisa’s first two pregnancies were rough and those children (another son and a daughter) were delivered prematurely. But an ultrasound taken 17 weeks into this pregnancy led to a discovery much more frightening: Their unborn son, Kaden, had a rare congenital heart defect. Instead of having two separate arteries to carry blood to the lungs and body, he had only a large one for the body, thus compromising the lungs. The condition is called truncus arteriosus.

Doctors downplayed the diagnosis, saying, “He’ll just have a few heart surgeries and he’ll be fine.” But then Lisa and Chris visited with specialists at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Denver.

“You don’t understand how bad this is,” doctors told them, “and we don’t know if we can fix this.”

Adding to their concern was the detection of a second serious issue, a leaky aortic valve.

Worst of all, the doctors described a Catch-22 situation: If Lisa delivered Kaden prematurely, he might be too small to operate on; if he went to full term, the stress of the birth would likely leave him in late-stage heart failure.

“I felt like a ticking time bomb,” she said. “We had no idea if he could be fixed or if he’d survive the birth.”

Kaden was born six weeks early, on Nov. 5, 2013, sharing a birthday with his father. Unlike Lisa’s other two deliveries, there were no complications, so she was able to hold him briefly, which she hadn’t been able to do with her son Nathan, now 12, and Emma, 7.

“I wanted to be able to touch my baby first before anyone else,” she said. “It was very special. He came out screaming at the top of his lungs and shaking his fists. And although he was a little grayish blue, you could tell he was ready for a fight.”

Still, Chris said, “We were afraid that in a few days we were going to be saying goodbye to him.”

Six days later, Kaden underwent a surgery to correct his congenital heart defect. Doctors used a conduit to reroute his blood flow. Doctors feared that Kaden wouldn’t survive the trauma of the nine-hour operation.

“The doctors were absolutely blown away,” Lisa said. “They started calling him Rocky because he was such a fighter.”

The leaky valve remained a threat. However, because Kaden was so small, doctors chose to wait to repair it.

“Those were the worst six months of my life,” Lisa said. “I wasn’t the mom with a child—I was the nurse with a patient. It was all about therapies and doctor’s visits—every single field of medicine. He was on oxygen and 12 medications and didn’t have the energy to eat, so we had to put a tube directly into his stomach.”

Kaden’s breathing eventually became more labored, adding to the urgency of repairing the valve. But doctors said he was still too small.

Searching for a solution, their surgeon, Dr. Max Mitchell, read an article about a case in which surgeons came at this same problem in a different way. The next day, he told Lisa and Chris about it. He acknowledged that it was “extraordinarily high risk” but he also seemed confident.

“Let’s do it,” they said.

The procedure took 13 hours. Finally, Mitchell appeared.

“He was smiling, and we rarely saw him smile,” Lisa said. “If he was feeling good, so were we.”

Kaden improved every month, becoming pinker and more energetic. He eventually went off supplemental oxygen and a feeding tube. His immune system continues to strengthen.

Four years later, he remains on blood thinners because of his mechanical valve. He’ll face more surgeries as his heart endures more wear and tear.

Source: Read Full Article