The human microbiome has been a hot topic over the last decade, with research pointing to disrupted bacterial communities as culprits for a host of maladies including irritable bowel syndrome, eczema, and autoimmune diseases. Most studies have focused on the microbiome within the human gut, but there is growing recognition that another oft-ignored bacterial community deserves equal attention — that found in the vagina.

Vaginal microbiome disruptions cause bacterial vaginosis (BV), which afflicts nearly 30% of reproductive-aged women around the globe and costs an estimated $4.8 billion to treat annually. BV doubles the risk of many sexually transmitted infections including HIV and increases the risk of pre-term birth in pregnant women, which is the second-leading cause of death in newborns. BV is currently treated with antibiotics, but it often recurs and can lead to more severe complications including pelvic inflammatory disease and even infertility.

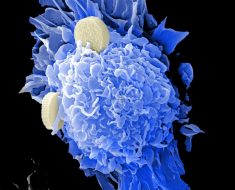

Just as probiotics are now being prescribed to treat gut issues, living biotherapeutics are being explored for the treatment of BV. However, it is difficult to conduct preclinical trials because the human vaginal microbiome is dramatically different from that of common animal models. Studies have found that Lactobacilli bacteria comprise more than 70% of the healthy human vaginal microbiome, but less than 1% of the vaginal microbiome in other mammals.

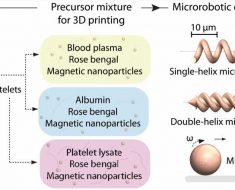

Researchers at the Wyss Institute at Harvard University have created a solution to that problem in the form of a new Organ Chip that replicates the human vaginal tissue microenvironment including its microbiome in vitro. Composed of human vaginal epithelium and underlying connective tissue cells, the Vagina Chip replicates many of the physiological features of the vagina and can be inoculated with different strains of bacteria to study their effects on the organ’s health. The chip is described in a new paper published in Microbiome.

Modeling the vaginal microbiome

The Vagina Chip was developed with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which aimed to create a biotherapeutic treatment for BV and move it into human clinical trials to decrease infections of the reproductive tract, prenatal complications, and infant death rates. particularly in low-resource nations.

Source: Read Full Article