American babies are at far higher risk of dying before their first birthdays than those in almost any other wealthy country. A big reason for those deaths, more than 21,000 each year, is that too many are born too soon.

For more than a decade, a pharmaceutical company has said it holds the key to helping those infants: a drug called Makena, which is aimed at preventing premature birth.

But the drug doesn’t work, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

A recent large study “unequivocally failed to demonstrate” that Makena reduced the risk of preterm birth, agency scientists explained in a 2020 memo. They recommended it be taken off the market.

The company has refused.

Instead, Covis Pharma, a Luxembourg company owned by private equity firm Apollo Global Management Inc., has continued to promote Makena, emphasizing a need by Black women, who are most at risk of preterm births.

Covis dismisses the results of the recent study since it included more white European women than Black Americans. It points to favorable older trials also disputed by the FDA, and it’s asking for more time to prove to authorities that Makena works.

The company’s continued push to sell the drug, as well as decisions by the nation’s top societies of physicians caring for pregnant women to continue to recommend it, has troubled and angered some doctors.

“We keep injecting pregnant women with a synthetic hormone that hasn’t been shown to work,” said Adam Urato, chief of maternal and fetal medicine at MetroWest Medical Center in Framingham, Massachusetts.

More than 310,000 women have taken Makena during their pregnancies since 2011 when the FDA rejected concerns of outside experts as well as one of its own scientists and approved the drug.

Among those women is Brittany Horsey, who had just received her weekly Makena injection in 2020 when she went into labor later that day—four weeks too soon.

She had a similar experience with the drug three years before with her second pregnancy. That child came six weeks early.

“It didn’t work,” said Horsey, 24. But the Baltimore mother still suffered from the side effects. She was hit with migraines and depression soon after starting the shots. The drug’s written label lists both as possible complications.

Makena’s lack of effectiveness has not reduced what Covis lists as the drug’s price—currently $803 per weekly shot, according to GoodRx, which tracks national prices set by drug manufacturers, or about $13,000 for the full course of injections often prescribed during a pregnancy.

And, despite the prescriptions, the rate of preterm births in the U.S. has continued to rise. Federal officials reported in March that 10.23% of the nation’s births were preterm in 2019—the fifth-straight annual rise.

Covis, which took over sales of Makena when it purchased AMAG Pharmaceuticals late last year, declined to make executives available for interviews. In a written statement, it pointed to a recent reanalysis of previous Makena trials that found evidence that the drug worked. The FDA says it already considered those previous trials and had not changed its finding that the drug was not effective. The company also said the drug is safe. It wants the FDA to allow it to keep selling the drug while it performs additional studies aimed at trying again to show that Makena helps patients or certain subgroups like Black women.

“The totality of data on … Makena supports its continued positive benefit-risk profile and the need for continued patient access,” the company said in a statement.

Covis added that the amount paid for Makena by “most payers” was “substantially less” than its listed price, which it claims is not accurate. It said, for example, it had recently reduced “the net price” of Makena paid by purchasers including state Medicaid programs, which cover the poor.

In August the FDA granted Covis a hearing to again review the evidence on the drug. A date for the hearing has not yet been set, which means thousands more women could be prescribed the drug before the agency decides whether to force the company to stop sales.

The story of Makena shows how pharmaceutical companies can use America’s drug approval system to make hundreds of millions of dollars from a cheap, decades-old medicine with questionable effectiveness and safety.

It also raises questions about the influence of corporate money on American doctors, even in an area of medicine that serves one of the most vulnerable group of patients: pregnant women and their children.

Urato points out that scientists don’t yet know the long-term effects of Makena on the children of mothers who get the shots.

“It’s crazy. This is a drug that has never been shown to have clinical benefit,” he said. “There is no way this drug should still be on the market.”

Seeing profit in an old drug

Doctors have been treating pregnant women with the synthetic hormone known as 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate, or simply 17P, since the 1950s. The natural hormone progesterone is essential for a pregnancy, but scientists have never been able to determine how adding a synthetic version might help women take their pregnancies to full term.

Developed in 1953, the drug was first approved under the brand name Delalutin. But in 1999, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the company then selling it, asked the FDA to remove its federal approval after many doctors lost interest in prescribing it.

The drug remained available, however, at compounding pharmacies that could make it at a doctor’s direction for about $15 a dose.

Executives at Adeza Biomedical in Sunnyvale, Calif., saw a financial opportunity when a government-funded study in 2003 found that the drug appeared to reduce the risk of preterm birth. The study, however, was not designed to show it reduced deaths or disability among infants—the true goal of doctors prescribing it.

The executives’ plan, according to the company’s public documents for investors: get the FDA to approve the cheap generic drug as a remedy for preterm birth based on the taxpayer-funded study. The company would then get an exclusive license to sell it and the ability to raise its price.

It was not hard to get the FDA to see the need for a drug that might reduce the risk of having a baby too soon.

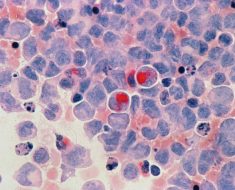

Infants born before 37 weeks—the official definition of a preterm birth—have a greater risk of complications. The earlier they are born the higher their risk of serious lifelong disabilities or even death. Lungs and digestive systems may not be fully developed. They can suffer bleeding in their brains.

Most at risk are Black babies. In 2019, more than 14% of births to Black women were preterm, compared with just over 9% of births to white women.

The corporate plan took years because FDA scientists and outside experts questioned whether the drug was effective and safe.

FDA scientists pointed out that studies where high doses of the drug were given to rats and other animals had not proven it was safe for human embryos, The Los Angeles Times found in a review of documents written by agency staff members. The scientists also warned there was not enough information on whether it might harm children’s learning, behavior and reproduction.

Another concern: There was only one clinical trial—the 2003 study funded by the government—that had shown the drug lowered the risk of preterm birth.

That study was flawed. The women taking the placebo had an abnormally high rate of preterm birth, which may have exaggerated the trial’s conclusion. Organizers of the trial later determined that the group given the placebo had been more at risk because a higher proportion of them had already had two preterm births.

In 2006 the FDA asked a committee of outside experts what they thought of the trial’s data. The panel voted 19 to 2 that the trial had failed to show that the drug reduced deaths or serious health problems in infants. And the committee agreed unanimously that there must be more study of whether it might cause miscarriages or stillbirths. It voted 13 to 8 that the safety data were “adequate” to support approval.

In the months and years after the meeting, the FDA repeatedly asked the company to gather more scientific data on the drug. That information answered some of the questions posed by the agency’s team of scientists reviewing the drug, but it never was able to convince one member of that group. Lisa Kammerman, an FDA statistician, repeatedly raised questions about the company’s plan over the years, including about the flaws in the 2003 study.

“From a statistical perspective, the information and data submitted … do not provide convincing evidence regarding the effectiveness,” Kammerman wrote at the top of her 58-page review of the drug in 2010.

Despite her opposition, the FDA approved Makena in 2011 under an accelerated regulatory pathway that has been questioned by experts.

The accelerated process is aimed at helping patients at risk of serious health problems who don’t yet have treatments. Under these regulations, the agency can approve a drug that is not yet backed by solid scientific evidence, allowing it to be prescribed while a study is done to confirm its benefits. Last year, the agency stirred controversy when it used the rules to approve the drug Aduhelm for Alzheimer’s disease despite a lack of data showing that it slowed dementia.

In Makena’s case, the agency said it would allow the drug to be sold while the company performed another clinical trial to show it actually saved infants from death or disability.

By then, the drug had been purchased by KV Pharmaceutical Co.

That additional trial—which ultimately showed the drug did not work—would take eight years. The price hike was immediate.

KV introduced the drug at a list price of more than $1,400 a dose, or nearly $30,000 for the 20-week course of injections needed during many pregnancies. Facing widespread outrage, KV soon reduced the price to $690—still more than 40 times what compounding pharmacies had been charging for what was then a nearly 60-year-old generic medicine.

Billion-dollar opportunity

Three years after the FDA approved Makena, yet another company acquired rights to the drug.

Executives at AMAG Pharmaceuticals said they were excited about the drug because KV had put it “on a remarkably strong sales growth trajectory,” according to a news release.

And they told investors they had a grander plan.

In a slide presentation in 2015, the executives described a “$1B Makena Market Opportunity.” They calculated that $1 billion in annual sales based on getting 140,000 pregnant women to agree to more than 16 injections during each of their pregnancies with net revenue earned for each shot of $425.

The “significant opportunity,” according to the slides, came from first trying to persuade more of the women at risk of preterm birth—those who had already had one child prematurely—to take the Makena shots.

Secondly, the company planned to find ways to increase the number of injections given to each pregnant woman from the average then of 13.5 injections per pregnancy toward the maximum possible of 21 injections. Its goal, according to the slides, was an average of 16 injections for each pregnant patient taking the drug.

To increase the average number of injections, AMAG said in the slides it would launch a program of “adherence/persistency”—that is, finding ways to keep women taking the shots even when they would like to stop because of side effects or other problems such as getting to the doctor every week.

AMAG said its “growth strategy” included having its marketing team focus on three key groups: physicians prescribing the drug, the professional societies that those doctors belong to and the nonprofit patient groups advocating for pregnant women and their children.

The company told investors that it had created “a publications committee” made up of “KOLs,” or key opinion leaders—a term the drug industry uses for physicians who may be able to sway the opinions of their peers. Companies often hire these doctors to write medical journal articles or give speeches to other doctors about their products.

The Times found that academic physicians hired as consultants by AMAG later wrote articles about how Makena was effective, how its side effects were little to worry about, and why doctors should not trust the cheap versions of the drug available at compounding pharmacies.

Covis told The Times it could not comment on activities of AMAG before it purchased the company. AMAG’s former chief executive did not respond to messages seeking comment.

One way AMAG kept in touch with doctors it considered opinion leaders was at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The group’s membership includes more than 5,000 physicians, scientists and women’s health professionals from around the world.

AMAG soon became a top financial supporter of the society and its events. At the society’s annual meeting in 2019, where doctors gathered at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, AMAG was listed in the program as the top corporate funder of the group’s foundation, giving at least $100,000. The Times found similar contributions going back to 2015.

The company is also listed as a “premier” member of the society’s corporate council. According to a society brochure on the program, a paid membership brings companies and the society’s physician leaders together “to focus on issues and initiatives of mutual interest in high-risk pregnancy.”

AMAG also gave money to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the nation’s largest professional association for doctors caring for pregnant women and their children.

The association’s website lists AMAG as an “industry partner.” The company gave at least $200,000 to the association in 2018, enough to become a sponsor of its President’s Cabinet.

Both the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have continued to support the use of Makena despite the lack of scientific data that it works.

Covis repeatedly cited the two groups’ recommendations for prescribing Makena in documents it submitted to the FDA demanding the drug stay on the market.

And in August, the association published new guidelines on preterm birth, continuing to recommend Makena for certain patients but not mentioning that the FDA had recommended it be pulled from the market. Those guidelines did not disclose that AMAG has been among the association’s top financial supporters.

Both the society and the association told The Times that the company’s payments had no influence on their recommendations for treating pregnant women.

Christopher Zahn, the association’s vice president of practice activities, said the group had told its members about the FDA’s action on Makena in other communications and did not see a need to include the information in the new guidelines.

“There is no role for industry in the development of ACOG’s Practice Bulletins,” Zahn said in a statement using an abbreviation for the association, “and ACOG neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of the Practice Bulletin.”

Kerri Wade, a society spokeswoman, said that the group has a strict conflict-of-interest policy and “industry has no input into the society’s clinical guidance, health policy initiatives, research, or the specific educational content.”

The company’s money didn’t just go to the medical societies. It went into the pockets of thousands of American obstetricians.

In 2018, AMAG gave cash or gifts to 5,800 physicians as its sales reps promoted Makena, according to a ProPublica analysis of a federal database.

AMAG’s marketing plan succeeded in significantly boosting prescriptions, but the company did not reach its goal of $1 billion in annual sales. An FDA analysis found that the number of patients prescribed the drug increased from 8,000 in 2014 to 38,000 in 2017. Sales reached $387.2 million in 2017 before starting to decline.

Even after the FDA said Makena should be removed from pharmacies, prescriptions for poor women covered by Medicaid are still being written at 55% of the rate of their high point in 2017, according to a December study.

The continuing support of Makena from the two professional groups of obstetricians has helped back those recent prescriptions—causing some doctors to question the groups’ acceptance of the corporate cash.

“Is academic medicine for sale?” asked David Nelson, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, and two other scientists in an article detailing AMAG’s payments to the two groups.

“We were taken aback by the amount of financial scope and influence in our specialty,” they wrote, adding that the “facts are resoundingly persuasive” that doctors should not prescribe Makena.

Adverse effects

Covis and doctors who are advocates of the drug say Makena has few side effects and it would not harm patients to continue sales while more research is done to try to show it is effective. “Its safety profile for the mother and baby are well established,” Covis said in a statement to The Times.

An FDA database contains more than 18,000 reports of patients experiencing adverse effects, ranging from rashes to serious problems like stillbirths.

A spokeswoman for the FDA said that “the presence of a report” in the database “does not mean the drug caused the adverse event.”

The agency continues to monitor the database, she said, as well as complications reported in clinical trials. And it has already required Covis to caution patients about problems such as blood clots, diabetes, hypertension and depression in the written label that comes with a prescription.

Stillbirths have been a concern since at least 2003, when the government trial showed a small but increased risk in women taking Makena. Two percent of volunteers taking the drug had a stillbirth compared with 1% of those taking the placebo.

Questions about the higher rate of stillbirths were raised by experts on an FDA committee that met on Oct. 29, 2019, to discuss the drug.

Julie Krop, an AMAG executive, told the panel that the company had an expert review each of the stillbirths suffered by women in clinical trials to determine whether it was caused by the drug.

The expert introduced by Krop was Baha Sibai, a professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston. According to a transcript of the meeting, Krop emphasized to the committee that Sibai was “independent” from the company.

“I looked through every one of these,” Sibai told the committee. “There was only one unexplained.”

Instead, Sibai said he had identified other factors such as a mother’s smoking or diabetes that would explain the stillbirths.

“And it is reassuring to see that, really, in either one of these studies, there was no signal that 17P increases stillbirth.”

Sibai had been one of the researchers in the 2003 study of the drug and during the meeting he was called on repeatedly to answer questions. His message: Makena works and is safe, and to take it off the market would have “catastrophic” consequences.

The Times found that AMAG had paid Sibai more than $14,000 in consulting fees and reimbursements for food and travel in the months leading up to the meeting.

After the meeting, the company’s payments to Sibai increased sharply. By early the next year, he had personally received an additional $50,000 from AMAG, according to a federal database of payments that pharmaceutical companies give to doctors.

The company was also giving Sibai’s employer large financial grants. AMAG paid the University of Texas Health Science Center a total of $215,000 in 2019 and 2020 for a research study of one of its experimental drugs that involved Sibai.

Deborah Mann Lake, a university spokeswoman, said Sibai wasn’t available to comment.

“It is our understanding that Dr. Sibai was compensated for the hours he spent preparing his testimony” on the 2003 study, Lake said. She pointed out that early in the eight-hour meeting Krop had told the committee that the obstetricians and other experts the company had invited to speak had been paid by AMAG for their time and travel expenses. Lake also said that the university was just one of 18 institutions that AMAG had paid for clinical trials of its experimental drug.

Krop did not respond to messages asking for her comment.

Scientists also have questions about Makena’s longer-term effects. They don’t yet know what harm the drug could cause over the years for mothers and their children.

Some researchers are concerned that Makena could increase the risk of cancers in the children of women who take it.

Barbara Cohn, an epidemiologist at the Public Health Institute in Oakland, and three other scientists published a study in November that found a higher risk of cancer among the offspring of 200 California women who had taken 17P during their pregnancies in the 1950s and ’60s when it was sold under the Delalutin name.

The mothers had agreed to participate in the Child Health and Development Studies, a group who received prenatal care between 1959 and 1966 at Kaiser Permanente in Northern California.

Using the California Cancer Registry, the scientists discovered the children of women injected with the drug were nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with cancer than those not exposed to the drug in the womb. The children’s rate of cancer of the brain, colon and prostate was especially high.

The findings “raise substantial concern” for prescribing the drug during pregnancy, the scientists concluded.

The Covis spokesperson said the study “offers no comparison to Makena” since it had been used in those earlier decades to “treat a different patient population for a different purpose.” The spokesperson noted that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists had told its members the study had limitations and “should not influence practice.”

The spokesperson also pointed out that the FDA’s decision to recommend the drug’s removal was not because of safety concerns but because of “conflicting efficacy data.” The company believes that both the 2003 study and the new trial confirmed the drug was safe, the spokesperson said.

Cohn said in an interview that her group decided to investigate the long-term effects of Makena because of its similarity to another synthetic hormone called diethylstilbestrol, or DES. Doctors began prescribing DES to pregnant women in the 1940s. Decades later, scientists found it could cause rare cancers in the mothers’ children. Some studies have found that DES may harm even the third generation.

“Hormones have very broad potential impacts on the body,” Cohn said. “Anything the pregnant mother is exposed to, her children are exposed to and her grandchildren are exposed to simultaneously.”

Lobbying to stop the FDA

A letter arrived at the FDA in May 2021.

Under a red letterhead logo depicting a mother and child, the Preterm Birth Prevention Alliance asked to meet with Janet Woodcock, the acting FDA commissioner, to share their members’ concerns about the plan to halt sales of Makena.

What the alliance did not mention in the letter was that Covis had paid to create the group.

Two months later, alliance members met with the White House Domestic Policy Council, where they left “encouraged” by the council’s “receptivity,” according to a note about the meeting on the alliance’s website.

They then soon met with staff from the office of Rep. Madeleine Dean, a Pennsylvania Democrat.

“We are so encouraged to find an ally and champion of maternal health in Representative Dean,” the alliance wrote on its website, “and look forward to continued engagement on this issue with her office.”

Tim Mack, a spokesman for Dean, said the alliance had not disclosed that it was funded by Covis during the July meeting. “We never knew the alliance was paid by the manufacturer,” Mack said. “That’s a troubling thing to find out.”

A White House official confirmed that the Domestic Policy Council and the Gender Policy Council had met with alliance members. Council members said they were not aware that money from Covis had created the group, according to the official.

Covis gave the money to create the Preterm Birth Prevention Alliance to a well-known consumer group in Washington, D.C., called the National Consumers League. The nonprofit group was created in 1899 by social reformers trying to improve working conditions. Among its founding principles is that “consumers should demand safety and reliability from the goods and services they buy.”

In recent years, the league has become more friendly with corporations. It invites corporate executives to pay to sit on its health advisory council. Before it was acquired by Covis, AMAG had paid to be a member of the council since at least 2017, according to the league’s website. AMAG is currently listed as a “platinum” funder—the designation for companies giving the most.

A spokeswoman for the consumer league did not answer a question from The Times on why it had not disclosed Covis’ funding in the letter sent to the FDA or in presentations it gave at the White House or to Dean’s staff. She pointed to a disclosure in a single sentence at the bottom of the alliance’s website and at the end of two brochures that said Covis had provided the funds to create the new group.

“We provide materials that disclose funding and include links to our website … at every meeting we attend,” she said in a statement. She added that Covis “is not involved in the strategic direction of the Alliance or its activities.”

Covis told The Times it had been “transparent in its activities with clinicians and advocates, which the company believes is in the best interest of patients.”

The correspondence that Covis and the alliance separately sent to the FDA mirror each other in key ways.

Like Covis, the alliance dismisses the results of the large new study, saying it did not include enough American Black women. And both the company and the alliance asked for another hearing where mothers, especially those who were Black, could testify on the need for Makena—a request the FDA granted in August.

The FDA has already repeatedly addressed the concern that stopping the drug’s sale could hurt Black infants. It explained last year that its scientists had analyzed the clinical trials, hoping to find that if they separated the data by the race of the mother they could find it helped some groups.

“After multiple analyses,” the agency said, it was “unable to identify a group of women for whom Makena had an effect.”

Drug companies have often used the voices of patients to try to influence regulatory decisions. AMAG sent patients to speak at the FDA committee meeting in 2019. The patients testified that they believed Makena had helped extend their pregnancies. Some disclosed that the company had paid for their travel and hotel expenses.

Daniel Gillen, professor and chair of statistics at UC Irvine, sat on the 2019 committee. He said he appreciated hearing from patients because it helped him understand how devastating it can be to have a child born prematurely.

But he pointed out that by far the majority of the patient volunteers in the large trial that prompted the FDA’s push to remove the drug went on to have a delivery at full term—whether they took the drug or the placebo.

Relying only on “the case study can be very dangerous,” Gillen said, referring to the stories of individual patients.

“The gold standard of evidence here is the randomized trial results,” he said. “We are still waiting on that clinically relevant data to say this drug is truly effective and outweighed by the potential risks.”

Stephen Chasen, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said he cares for many minority women at risk of preterm birth. He said it is hard to tell his patients that there is no drug he can recommend.

“But what would be worse than being honest with patients,” he said, “would be for us to mislead them by recommending an intervention that has no evidence that it works—which is essentially, what is being done in prescribing Makena.”

Help beyond Makena

There are other ways to reduce the risk of having a baby too soon.

When Cochrane, an international health care research group that doesn’t accept money from companies, set out to determine how pregnant women could avoid preterm birth, Makena did not make its list. The group had gathered and analyzed dozens of studies from around the world on interventions aimed at extending pregnancies.

At the top of the list was care delivered by midwives, which Cochrane said studies had shown provided a “clear benefit” in reducing the risk of an early birth.

Poor maternal care, especially of Black, Native American and Latina mothers, has long been associated with preterm births.

Almost 10% of Black mothers received dangerously late or no prenatal care at all in 2019, according to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That was more than double the rate for white mothers.

In South Los Angeles, Kimberly Durdin, a Black midwife at Kindred Space LA, said a visit for pregnancy care in the mainstream medical system may last just five minutes. In comparison, at a birthing center, she said, midwives become partners with their patients throughout their pregnancy and birth. Women are encouraged to ask questions, she said, and the visits are long enough for advice on nutrition and even how much water to drink.

The medical system, Durdin said, “does not allow enough time to deliver the care people need to avoid slipping through the cracks.”

Horsey, the mother in Baltimore, said that when she recently got pregnant again the doctor and staff at the clinic she visits told her she should start the Makena shots.

She reminded them of the side effects she had suffered from the shots in two earlier pregnancies and how, despite taking the drug, she had still delivered her babies too soon.

Horsey said she told them she had decided not to get the injections with this pregnancy—and they initially pushed back.

“I felt my opinion did not matter,” she said.

Horsey ultimately convinced them she did not need Makena. On Jan. 7, she gave birth to a girl at 38 weeks, which is considered full term.

Durdin said she had heard similar stories from Black women who felt their doctors didn’t listen when they raised concerns.

She pointed out that obstetricians prescribing Makena are protected from bad outcomes because they can show they are following guidelines issued by their professional societies.

Those professional groups should be working to change the system, Durdin said, “so people can have better care and more time with their practitioners.”

Source: Read Full Article