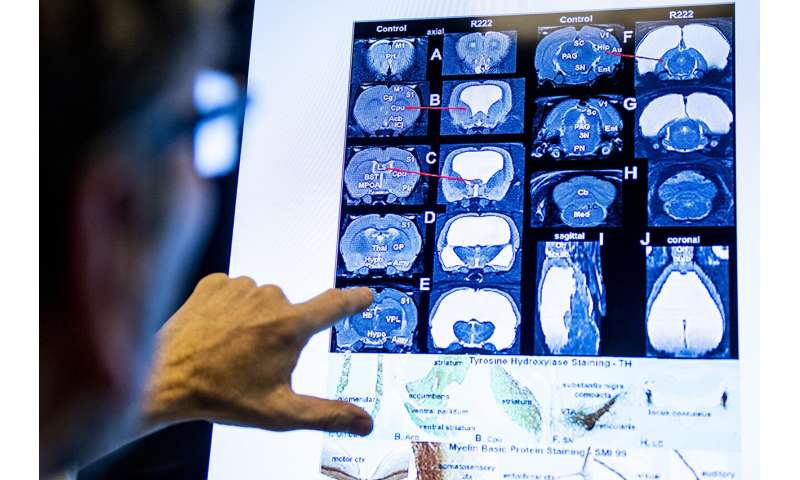

One day, a scientist in Craig Ferris’s lab was scanning the brains of very old rats when he found that one could see, hear, smell, and feel just like the other rats, but it was walking around with basically no brain—and likely had been since birth.

This rat, named R222, did have a brain. But its brain, affected by a condition called hydrocephalus, had compressed and collapsed as it filled with fluid, and many of the functions that would ordinarily be carried out in the brain had relocalized to areas that weren’t taken over by fluid.

This provided the tools for Ferris, a psychology professor at Northeastern, to investigate how powerful the brain remains, even when tight on space. This, he says, might even influence the ever-present goal of machine learning: How small can you be and still get the job done?

Pretty small, it turns out, at least in R222’s case, but this efficient use of space is dependent on the brain’s capacity to reorganize. This ability, known as neuroplasticity, is a widely documented phenomenon, but such an extreme example was rare, says Ferris.

In R222’s case, he says, the processing of visual input “was distributed over much of the remaining brain, and the same thing with smell and touch.” What at first the scans suggested to be a brainless rat was actually a rat with a brain that had been pushed out of the way and flattened like a pancake—and kept working.

Ferris’s lab, the Center for Translational Neuroimaging, originally received R222 as part of a group of test animals from Alexion Pharmaceuticals for a study on aging, and Ferris’s team kicked off the study as it would any similar project: by taking preliminary scans of the animals. While doing so, Ferris’s colleague flagged something on the computer. “And when I looked at the screen,” says Ferris, “what I saw, basically, was a rat without a brain.”

In Ferris’s words, R222 was “one of nature’s miracles,” since living for two years (like living for more than 70 human years) is unlikely with such a severe deformity. Given that, he says, “we had this unique opportunity to try to understand how this animal survived,” a feat made more impressive by the fact that R222 basically acted like any other rat: Successful adaptation to this extreme abnormality suggested the animal had it since birth.

First, though, the team had to measure just how similar R222 actually was to the other rats in the cohort. To assess memory, the researchers placed each animal in a Plexiglas box to observe how it responded to a new space and the objects within it. They then observed the rats navigating a maze in a further display of memory, as well as of spatial learning skills, and measured physical behavior as the animals walked a balance beam.

In all but one of these tasks, R222 performed just like the other rats.

The exception was exploring a novel environment—the other rats moved around and showed interest in their surroundings, and R222 stayed put. On its own, though, the latter behavior wouldn’t indicate something debilitating, says Ferris; this failure to explore is common among anxious animals. So, beyond the possibility that it experienced heightened anxiety, R222 functioned normally—and, importantly, appeared normal on sight.

And yet, brain areas as seemingly crucial as the hippocampus, which processes memory, were so distorted that Ferris and his team couldn’t even identify them on sight. It was only after they traced chemicals in the brain that they were able to verify that, indeed, the hippocampus was that squished, displaced object pushed toward the back of the brain.

“The lower part of the brain stem had everything collapsed in it,” says Ferris. “This animal just defaulted to what evolution gave it in the beginning, along with all the other animals, to help it survive.”

For rats, that’s enough; as Ferris says, “most of their life is spent working through their nose.” But could humans, too, get by with less brain power?

It’s possible, says Ferris. In fact, in a case to which Ferris and his coauthors make reference in their study, a neurologist found that having an IQ of 126 and a brain that’s mostly fluid aren’t mutually exclusive.

Source: Read Full Article