As scientists continue searching for treatments to some of the most complex diseases and conditions, they’re increasingly looking to our gut.

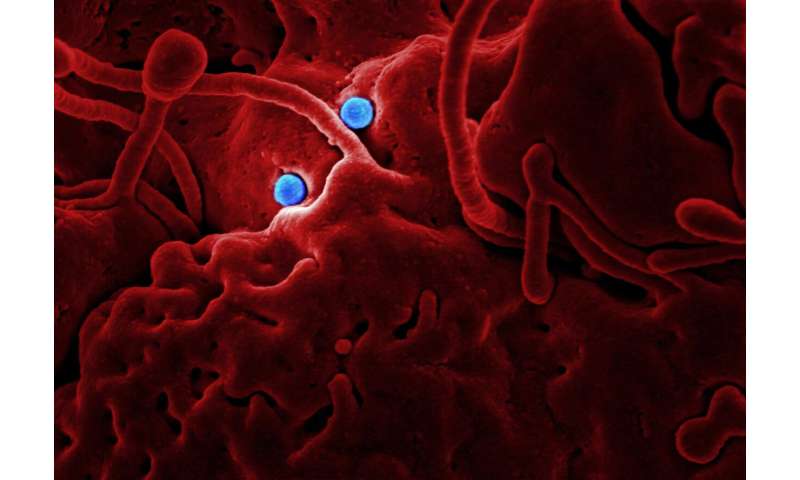

The human gut microbiome contains trillions of bacteria that play important roles for the proper functioning of our bodies. But those bacterial colonies went relatively unexplored until recently, when new computational tools made it possible to understand their makeup in more detail.

Finch Therapeutics is one of a number of companies trying to turn that new perspective into new treatments. The company is leveraging its deep connections and expertise in the field to reach a number of milestones in microbiome therapeutics—and it’s outpacing older, better-funded competitors in the process.

The company recently became the first to show a microbiome therapy could reach its primary goals in a Food and Drug Administration trial for patients with Clostridioides difficile infection (C. diff).

Now, as the research community continues to discover connections between gut health and metabolic, immune, and cognitive functions, Finch is developing a broad group of drugs aimed at conditions including chronic hepatitis B, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and autism spectrum disorder.

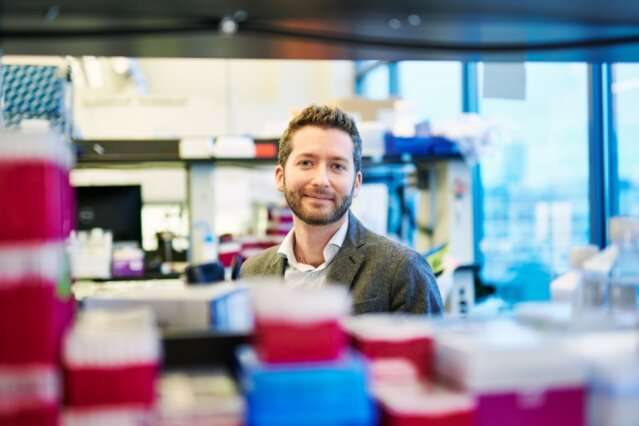

“The biology [around gut bacteria’s influence on health] is fairly complex, and we’re still in the early days of unraveling it, but there have been a number of clinical studies that have reported benefits to restoring gut health, and that’s our north star: the clinical data,” Finch co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Mark Smith Ph.D. ’14 says.

A path unplanned

Smith always thought he’d spend his career doing academic research. Then, while pursuing his Ph.D. in microbiology at MIT, a family member contracted C. diff, a potentially life-threatening infection that can cause diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain. Smith saw his relative gradually grow discouraged with conventional treatment options as he went through seven unsuccessful rounds of antibiotics over the course of one painful year.

Around that time, a clinical trial showed the promise of using stool transplants to restore gut bacteria in people struggling with C. diff, improving their symptoms. Still, there were very few places collecting stool samples or conducting the procedure at the time. Increasingly desperate, Smith’s relative ended up conducting the stool transplant himself with the help of a friend and an at-home enema kit. The procedure was successful, but risky, and is not rcommended by doctors.

Smith knew his relative was not alone—about a half million people contract C. diff each year—so he set out to expand access to medically certified stool transplants. The effort led to OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank that collects and screens stool samples, then ships the formulations to hospitals to conduct transplants. Along the way, Smith partnered with OpenBiome cofounders Andrew Noh and James Burgess, who were attending the MIT Sloan School of Management; Zain Kassam, a postdoc who had worked with Smith in the lab of MIT Professor Eric Alm; and Carolyn Edelstein, now the executive director of OpenBiome, who is also Smith’s wife.

Today OpenBiome works with around 1,300 health care providers across the country and has helped treat about 55,000 patients struggling with C. diff, making it the largest stool bank in the world. OpenBiome also facilitates research into the microbiome, uncovering surprising links between the bacteria in our guts and a range of complex conditions like depression, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and autism.

The research was enough to convince Smith he needed a new way to help the microbiome field reach its full potential. He founded Finch Therapeutics in 2014 with many of his colleagues from MIT and OpenBiome, including Noh, Kassam, and Burgess.

Since then, the company has focused on developing drugs that mimic as closely as possible the bacterial makeup of the stool transplants used in some of the field’s most promising studies.

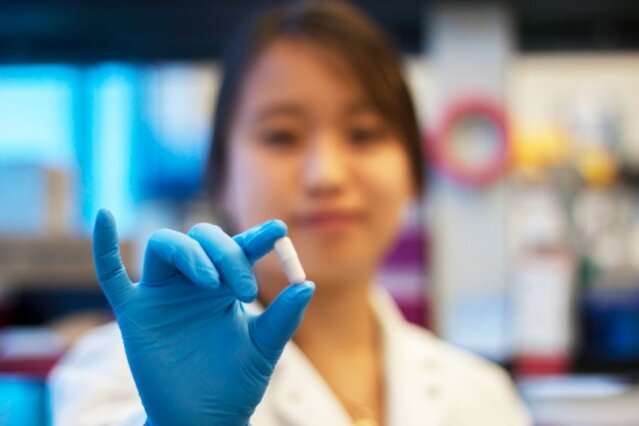

Finch’s drugs are made by collecting a stool sample from a vetted donor, screening that sample, processing it to extract the microbial strains, freeze drying the strains, then, following some additional testing, putting it into a pill capsule.

By closely following the methodologies of intervention studies, Finch hopes to safeguard against any major setbacks in clinical trials and become the first company to earn FDA approval for a microbiome-based treatment.

Last month, Finch achieved a major milestone in that direction when it announced preliminary phase 2 results for its oral C. diff drug. The company says it was the largest placebo-controlled trial for an oral microbiome drug to date, and the first to meet its primary efficacy targets in a pivotal trial.

“The first chapter in this field, and our history, has been validating this modality,” Smith says. “Until now, it’s been about the promise of the microbiome. Now I feel like we’ve delivered on the first promise. The next step is figuring out how big this gets.”

Realizing the potential of a promising field

Companies hoping to create treatments from our nascent understanding of the microbiome must navigate some uncertainty around the biological mechanisms that are behind the links between our guts and a range of diseases. Still, those connections are being reinforced in new studies all the time.

“There’s a wide range of indications that are potentially related to microbiome,” Smith says. “We’re just starting to figure out what some of those are. The ones where there’s more research, we understand [the underlying biological] mechanism, and there’s likely going to be this broadening ring of indications we discover as the field continues to mature.”

Finch is planning another, larger study to confirm its C. diff results before submitting the drug for FDA approval. In addition, by the middle of next year, the company will have data on the effects of another oral microbiome drug for children with autism and gastrointestinal issues. Next year it will also complete a trial using the same C. diff drug to help patients with chronic hepatitis B.

“Our view is there are 42 billion doses of antibiotics administered every year, and we think they’ve driven really profound changes to this microbial organ system. We’d be surprised if restoring that functionality doesn’t turn out to be important for a lot of different indications,” Smith says.

Smith notes there are 300 ongoing clinical trials exploring connections between the microbiome and diseases like Alzheimer’s, Crohn’s disease, and multiple forms of cancer.

Source: Read Full Article