Disabled people losing chance to live independently due to medical aid rip-off prices – such as £136 for plastic bottle and straw – campaigners claim

- Disability aids for walking, special beds and wheelchair repairs not free on NHS

- Firms accused by Disabled Living Foundation of cruelly hiking medical aids costs

Disabled people are being deprived of the chance to live independently because profiteering firms are cynically inflating the prices of medical aids, campaigners claim.

Many crucial disability devices, such as walking aids, specialist beds and wheelchair repairs, are not covered by Government funding schemes or NHS care.

In almost all cases, cash-strapped families are forced to turn to private companies to access these aids and pay for them out of their own pockets, with the price often reaching thousands of pounds.

Campaigners have raised concern over the practices of some firms, which they argue are cruelly hiking the costs of basic medical devices. ‘The spiralling costs of disability aid products is a huge issue,’ says Rachel Oakes, occupational health services manager at the charity The Disabled Living Foundation.

‘Whenever a disability label is put on products, companies add noughts to the end of the price. There’s a huge difference between what these devices cost to make and what providers sell them for.

‘It’s clear that many are realising how profitable this business can be.’

ESSENTIAL: Fraser Simmonds, nine, needed a £15,000 wheelchair to get around as he has the degenerative muscle condition Duchenne muscular dystrophy

This newspaper has learned of a series of cases where firms have attempted to charge well above market rates. One major UK supplier told a family from Essex that the cost of replacing the battery in their disabled nine-year-old son’s wheelchair would be £560, when the mother was able to find the same battery on sale for £50.

A disabled 78-year-old from Cheshire was also told by a specialist firm that the wheelchair ramp he needed to get out of his house would cost £6,500, but a local joiner carried out the adaptation for just £900.

In another case, a woman from Northern Ireland with a muscle-wasting disease had to spend £136 on a plastic water bottle – a simple container with an extended straw and an attachment which clips on to a wheelchair – which was triple the price charged in the US.

‘Everything is more expensive for disabled people,’ says Fazilet Hadi, head of policy at Disability Rights UK. ‘There is almost a monopoly within the sector – equipment and adaptations are often procured through a small range of companies, and installed by a smaller range of specialists, often at a higher mark up than conventional home upgrades.

‘Companies often claim they are catering to a small, specific group of people. But a fifth of people in the UK are disabled in some way – it’s a big market.’

About two million people in the UK with disabilities need their home to be accessible – fitted with ramps, handrails, wide door frames and downstairs shower rooms – so they can move around safely. Just over half of these are wheelchair-users, according to NHS figures.

DISABILITY FACT

For a quarter of families with disabled children, extra costs amount to more than £1,000 every month.

Most local authorities have a budget to pay for small changes to disabled people’s homes, provided they cost under £1,000. But any further costs require what is known as a disabled facilities grant. The means-tested scheme provides up to £30,000 for home adaptations in England. Residents in Wales can receive up to £36,000, while the grant isn’t available in Scotland. Most councils won’t provide the extra cash if families have savings of more than £6,000.

People are also waiting longer than ever to receive these funds.

Last year, The Bureau Of Investigative Journalism found people were waiting up to 18 months to get a grant signed off. This is largely due to a lack of occupational therapists, who have to visit the property and approve changes before a grant is approved.

‘Since the pandemic, we’ve seen the number of occupational therapists go down and the number of disabled Britons go up,’ says Lauren Walker, an adviser to the Royal College of Occupational Therapists. ‘People are waiting longer than ever to get a grant, and the effect is that more and more are having to get these changes done privately.’

As a result, Ms Walker says families fork out for housing adaptations which are often inappropriate for their needs. ‘I’ve heard of a number of occasions where someone paid upwards of £10,000 for adaptations, and then went to the council to get it to cover the costs.

‘When the council visited, it was discovered that the contractors had fitted something which wasn’t at all what they needed, so the council often wouldn’t cover it.

‘In one case, the company turned a bathroom into a wetroom for someone with mobility issues. But they put in a step, which made it completely pointless as the woman was in a wheelchair.’

Another problem area in terms of financial support is the upkeep of wheelchairs. Although the NHS provides them for free, it won’t cover the costs of adjustments.

One patient affected is nine-year-old Fraser Simmonds, who has the degenerative muscle condition Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

His mother Shelley, 43, says when he was four, the family had to spend £15,000 on a motorised wheelchair after the NHS refused to pay.

‘We were told that at that age he could be pushed in a standard wheelchair,’ she says. ‘We wanted the wheelchair so he could socialise with friends and not rely on someone else’s help. But it was denied because apparently social interaction is not a medical need. I couldn’t believe how much it cost – we could’ve got a new car at that price.’

Now Fraser has outgrown the wheelchair, the NHS has agreed to pay for the replacement.

However, only the most basic features are covered by the health service. Important add-ons, including lights so Fraser can see the pavement when out with his parents in the evening, and a riser – an adjustable seat which lets him reach high-up objects – have to be paid for by his parents. The lights cost £250 while the riser was £750.

‘It’s disappointing we had to pay for simple things that help give him some independence,’ says Shelley.

When the battery for Fraser’s wheelchair died, the NHS told Shelley there were no funds to repair disability aids. The company which makes the chair informed her that replacing the battery would be £560. But friends were able to find the same battery on Amazon for £50.

‘I’m on a group chat with other people in the disabled community, and so much of the conversation is just sharing tips about where to find the cheap stuff,’ says Shelley.

Michaela Hollywood from County Down, Northern Ireland, lives with a rare degenerative condition called SMA2 which weakens her muscles. The 32-year-old charity worker requires a wheelchair and struggles to hold items.

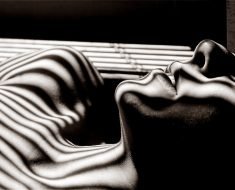

Last year Michaela attempted to order a cup which would allow her to drink water unaided. Known as a Giraffe Bottle, it has a long, flexible straw and clips on to a wheelchair.

The product costs roughly £47 in the US, but UK supplier NineLife sells it for £136, which it claims is a markdown from the original price of £224.

NineLife did not respond when approached for a comment.

Giraffe Bottle (pictured) it has a long, flexible straw and clips on to a wheelchair which allows disabled people to drink water unaided

Giraffe Bottle costs roughly £47 in the US, but UK supplier NineLife sells it for £136, which it claims is a markdown from the original price of £224

DISABILITY FACT

The total annual spending power of UK families with at least one disabled person is an estimated £274billion.

Michaela says that as there was no other option online, she was obliged to pay the high price. ‘That much money for a plastic cup? I was flabbergasted,’ she says.

In many cases, families are told they must purchase the expensive specialist equipment before a loved one can return home from hospital or a care home.

The family of 98-year-old Trudi Clinton say they had to pay nearly £1,500 for an adjustable bed which was used for only a few months. Her granddaughter Justine Glenton, 57, says the family wanted to remove Trudi from her care home in Yorkshire following the isolation she faced in the pandemic. ‘She wasn’t allowed outside for a year. It was terrible,’ says Justine.

But staff told the family their grandmother could leave only if there was an adjustable bed at home – one which could be raised or lowered so she could safely get in and out. Just one local company could supply it.

‘The only option to get her out of the care home was to pay £1,500 for a bed,’ says Justine, ‘We barely ever used the adjustable feature. These companies have you over a barrel because there is no other choice.

‘A few months later, my grandmother fell in the bathroom and broke her hip. The NHS supplied us with another bed for free which had an air mattress to prevent bed sores while she recovered.

‘We’ve decided to keep it and sell the adjustable bed.’

But this, it turns out, isn’t simple. Justine says they put it up for sale online but no one has bought it. ‘Not even for a few hundred pounds, so it’s just sitting unused,’ she adds.

Experts say that when people return barely used disability aids to the NHS, a significant amount are thrown away every year, so items such as walking frames and sticks simply go to waste.

‘The worry is that if these items get repurposed but they break and injure someone, then the hospital will be held liable, so they don’t take any risks,’ says Jan D’Arcy, a retired specialist dementia carer who still does volunteer work at care homes. ‘I’ve even seen wheelchairs thrown in the bin, despite the fact that they are perfectly usable. Some of it is even still in its NHS packaging.

‘It’s heartbreaking when you consider how much money people spend on these things.’

Source: Read Full Article