Twenty years ago, as sirens pierced the calm New York City morning and Americans struggled to absorb the TV images of smoke wafting from the World Trade Center, emergency medicine physicians mobilized to do what they train for: save lives. That mission affected them in ways they couldn’t have imagined, forever shaping their medical careers.

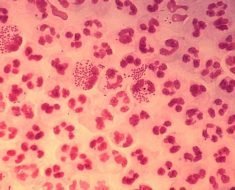

Healthcare workers outside St Vincent’s Hospital in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attack.

At the hospital closest to the twin towers — New York University (NYU) Downtown Hospital (now New York-Presbyterian Hospital) — emergency physician Antonio (Tony) Dajer, MD, heard an overhead page for respiratory therapy, which was odd because, as the attending physician on duty in the emergency department (ED), he usually sent out those pages. A paramedic standing outside the hospital had received a police call about a plane striking one of the towers, just four to five blocks away. Two nurses taking a smoking break heard the plane hit.

“We knew right away that we were going to get casualties immediately,” says Dajer, who is now assistant professor of emergency medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College and still oversees residents at New York-Presbyterian. “We had 10 minutes to get set up. That was a mad scramble.”

Dr Antonio Dajer

The emergency room (ER) was small — just 10,000 square feet with a typical load of 100 patients per day. But the close-knit comradery of the hospital staff proved to be an asset as they set up medical stations and took up designated duties. Dajer created a triage area outside the ambulance bay. He had gained vital disaster response experience when he worked in the ER during the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, and the ER had just completed a disaster drill a few months before.

At first, everything was oddly quiet. Then the patients came — running, walking, limping, and on ambulance stretchers. “It’s like something out of one of those stampede scenes where suddenly a mob of people came charging into the ER,” he recalls.

Additional doctors, nurses, and other hospital workers came, too, and Dajer directed them to posts. There was a suture station, an asthma station, and a trauma area. He estimates the ER treated about 400 patients in the 2 hours after the first plane hit, some of them severely burned as fiery jet fuel plunged down elevator shafts into the tower’s lobby.

The thunderous collapse of the towers brought a new threat from the thick dust cloud. As people rushed to the hospital — gasping, coughing, eyes tearing — the ER improvised a kind of air lock, closing the outer door before opening an inner door. Still, smoke was everywhere. “There was this haze I still remember,” says Dajer. “Everything became fuzzy.”

Within 24 hours, an estimated 1500 people were treated in the ER, many of them for effects of the smoke and dust. (It became impossible to keep records of every person treated for stinging eyes or minor injuries, Dajer says.)

No one could have practiced such an incredible scenario in mock drills, but the clinicians and hospital employees all knew their roles — and, importantly, that they were there for each other, Dajer says. “For me, one of the biggest lessons of 9/11 is that people really do rise to the occasion,” he says. “People will dazzle you.”

Triage at the Ferry Terminal

Michael P. Jones, MD, was just returning from his morning jog when he heard a cacophony of sirens. As they grew louder and more frequent, he tried to call the chief of the Central Park Medical Unit, where he volunteered to provide care within the park. At the time, Jones was an emergency medical technician, a junior at Columbia University, and was considering a career in medicine.

No one answered the phone, so he headed for the unit’s base of operations, where he ended up riding in the flatbed of a pickup truck carrying supplies to the World Trade Center site. They arrived just as the first tower fell in an enormous plume of gray smoke.

The scene was chaotic. Jones began helping assemble triage tents until a firefighter directed him to a treatment and triage center being established at the ferry terminal. As they aided first responders injured during the rescue effort, Jones and the other emergency workers still didn’t know the broader story behind the disaster.

Dr Michael P. Jones

“We were all just working in this abyss of not knowing what was happening,” says Jones, who is now vice chair of education and residency program director for the emergency medicine department at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and of the Jacobi and Montefiore Medical Centers in the Bronx. “We expected lots of [rescued] patients, but we didn’t have them.”

One moment lingers in his memory: He took a police officer who had a broken ankle and was in respiratory distress on a ferry to Staten Island, where an ambulance brought him to a hospital far from the scene. The officer was upset because he had become separated from his partner.

“I didn’t actually do much for him medically,” recalls Jones. “What I did was just talk to him during that ferry ride.”

Emergency medicine is about providing help “in the worst moment of people’s lives. I was there with others to help and support them, and that was something incredible,” he says. “That made me very convinced that emergency medicine was the path I wanted to take.”

The Stressors Build Up

Dr Jenny L. Castillo Cato

Jenny L. Castillo Cato, MD, was sleeping late, in preparation for an ED shift that began at noon, when a friend called and woke her. The friend was driving on the New Jersey Turnpike and saw smoke coming from the World Trade Center. Castillo turned on the television just as the second plane hit — and she immediately prepared to head into work.

Then an emergency medicine resident at Jacobi, she helped get the ED ready for an onslaught. Existing patients were either admitted or discharged. ED staff set up a hazmat shower to protect against toxic contamination. They set aside an area for orthopedic doctors and another for trauma surgeons. Then they waited.

“It was very, very eerie,” says Castillo, who is now an associate professor of emergency medicine and attending physician at Columbia University Medical Center. “There was a huge feeling of sadness, helplessness. We wanted to help, and we were ready to help — and there was just no one to help.”

Eventually, about 30 stunned and dust-covered people straggled in, having walked from Manhattan to the Bronx. Their physical issues were minor. “They clearly were fine if they could walk that far,” Castillo says.

The next night, she volunteered to work in a mobile medical unit at the Ground Zero site, mostly providing care to firefighters, police, and construction crews in the recovery zone who sustained cuts and bruises and other minor injuries. At one point, she decided to survey the damage and went to what remained of a walkway from the West Side Highway.

She saw huge beams twisted in the rubble and a fire truck flattened like a pancake. Two or three inches of dust covered everything, like a gray snowfall. And there was an enormous hole where the tallest building in the world once stood.

The air smelled acrid, a mix of burnt metal and burning flesh. “I will never forget that smell,” she says.

In the years after, Castillo responded to numerous tragedies large and small, as all emergency medicine physicians do. The death of an 8-year-old girl shot in a drive-by shooting was particularly devastating, evoking that feeling of helplessness. She suffered from burnout and almost left emergency medicine.

Today, Castillo is director of wellness for the emergency department. She coordinated wellness challenges and helped establish a break schedule to ensure physicians have time to decompress. During the pandemic, she pushed for a clean space where physicians could eat together safely.

The stressors stack up and physicians need a way to relieve them, she says. “It’s a very difficult job, and it really does physically and mentally affect you,” she says.

Making a Personal Connection

Dajer wants everyone to know a positive statistic: “99% of the people below the impact [of the planes] survived 9/11.” They were evacuated and treated due to the heroic response of firefighters, police, transit workers, and emergency medicine teams.

Still, it was hard for him to process what happened that day. Dajer yearned to know more about the patients who came through the ED doors. A friend connected him with the family of a man who had traveled to New York City on business and happened to be walking near the towers when they were struck. He was hit with burning jet fuel and falling debris.

Dajer visited the man in ICU and met his wife, who expressed her gratitude that Dajer and his colleagues had kept her husband alive. “In a way, she helped us heal, which was extraordinary,” he says.

The man died of his injuries about 3 months after 9/11, but Dajer remains in touch with the family. Beyond the emergency drills and plans, this is what matters, he says. “One thing I regret [in the ED] is not deliberately assigning people to just hold a patient’s hand, to get to know them and have some kind of emotional bond,” he says.

As he shares advice about disaster response, Dajer mentions that powerful emotional aspect of care: “There’s always time to hold people’s hands.”

Michele Cohen Marill is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta. She has written for Wired, STAT, Health Affairs, and other publications. She can be reached at [email protected]

Where were you during the 9/11 attacks and how did it impact your life? Please share your experiences as we reflect on that day 20 years ago.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article