Ingenious tricks to boost your memory! Don’t sit down, don’t multi-task and be emotional are among tips proven by the latest research

Memories are not only essential for our day- to-day ability to function, they are key to our relationships and signposts to events in our lives.

Now scientists have found that the memories — specifically, the type of memories our brain chooses to store — can influence our risk of developing certain conditions.

For instance, it is thought that the brains of people with anxiety and depression have a bias towards storing negative memories over positive ones.

‘And this can be a vicious circle because if your focus is on negative aspects then that exacerbates your depression,’ says Robert Logie, a professor of human cognitive neuroscience at Edinburgh University and an authority in the field of memory.

This, in turn, has a significant impact, as highlighted in recent research by King’s College London and Exeter University. This found that people over the age of 50 who were anxious or depressed at the peak of the pandemic experienced a drop in memory function that was equivalent to the effects of six years of ageing.

‘We think of memory being a problem in dementia but it’s a problem in many disorders of the brain, including post-traumatic stress disorder and mental health problems,’ says Jack Mellor, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Bristol, who is researching new targets for drug therapies to improve memory.

Memories are not only essential for our day- to-day ability to function, they are key to our relationships and signposts to events in our lives. Now scientists have found that the memories — specifically, the type of memories our brain chooses to store — can influence our risk of developing certain conditions

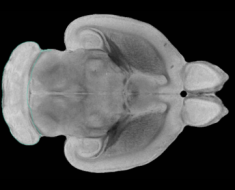

A memory is not a passing emotion or idea: it’s a physical thing, formed of connections called synapses that form between the nerve cells — or neurons — in your brain. Each synapse has a neurotransmitter (a signalling molecule) that fires chemical messengers across the gap to the next neuron. These connections between the neurons multiply in the hours after an event, before the memory is filed away until you want to recall it.

The less you recall something the weaker these synaptic connections become, and the memory itself becomes harder to bring clearly to mind. When you recall something, more of these connections will fire until a full memory is completed.

Scientists are still unravelling many of the fine details about how memories work but recent breakthroughs suggest we may be tantalisingly close to finding simple ways to improve our recall.

In one of the most unusual discoveries, research teams from Queen Mary University of London and universities in China and Finland have found that the gut microbiome — the community of bacteria and other microbes that live inside us — may influence the strength of our memories.

The findings, published in Nature Communications in November 2021, which were based on bees — noted for their ability to recall the location of nectar hotspots (see box, right) — opens the door to the possibility that we could influence the efficiency of our memory by simply ‘feeding’ the gut bacteria found to boost our recall most effectively.

Diet high in fat can affect the brain

Dementia — and with it memory loss — is the disease we now fear most, surveys show. But there are other, more everyday factors that can reduce our recall, from stress to hormonal factors such as the menopause (oestrogen increases levels of an enzyme needed to produce acetylcholine, a brain chemical critical for memory) and even what we eat and drink.

For instance, studies have suggested that a diet high in fat and sugar can impact on memory — one explanation being it triggers inflammation in the brain. How quickly the effects are felt is unclear — but studies suggest that you can reverse at least some of the damage.

For example, research on mice published earlier this year in the journal Aging and Disease found that a fatty, sugary diet led to changes in areas of the brain key to memory — but those changes could be reversed with eight weeks of healthy eating.

A sedentary lifestyle will also have an effect. A study by the University of California, Los Angeles, involving 35 healthy adults, found that those who spent the most time sitting tended to have thinning of the medial temporal lobe — another area of the brain crucial to memory — reported the journal PLoS One in 2018.

Depression linked to lack of recall

A lack of mental activity can also have quite an immediate impact.

When researchers from the University of Naples put 150 students through cognitive tests before and mid-pandemic, they found that their recall had declined.

Professor Logie says one problem is not having enough interesting things to remember.

‘Memory deals with novelty better than the mundane,’ he says. ‘Say you go to the same restaurant or park your car in the same spot every day, you wouldn’t remember any one of these things in great detail.

‘What happens is that our brain efficiently forgets a lot of the details but retains the common features. During the pandemic, much of what we did became humdrum so there was nothing novel to latch on to and our memories suffered.’

This may be why people with depression can develop a poor memory, he says. ‘When you are depressed, you tend to do less and have fewer fresh experiences.’

The good news is that getting older doesn’t inevitably mean you will become forgetful.

‘Age affects different people in different ways,’ says Professor Logie. While some age-related decline is inevitable, he says, ‘there are plenty of sharp 96-year-olds — look at the Queen — but others show deterioration much earlier.

‘It can be that age-related health problems, such as heart disease, play a part as this reduces oxygen flow to the brain — memory is dependent on the healthy function of the brain — but if the person is generally healthy, the impact isn’t that severe just with age alone.’

The strength of your memories ultimately comes down to simple biology — the strength of connections between those neurons in your brain.

The less you recall something the weaker these synaptic connections become, and the memory itself becomes harder to bring clearly to mind. When you recall something, more of these connections will fire until a full memory is completed

As Professor Mellor explains: ‘Nerve cells have arms that connect to others, and those connection points are adaptable: they can change how strongly they grasp the next cell.

‘Each nerve cell makes tens of thousands of connections to other nerve cells,’ he adds. The synapses drive those connections — the connections themselves may become stronger or weaker according to how much you ‘use’ the memory.

What, if anything, can you do to support those connections?

‘The more you recall a memory, the easier it is to retrieve,’ says Chris Bird, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Sussex University.In fact, there are many elements that affect how firmly something is committed to memory, such as whether it has any connection to any other memory — connected memories are easier to recall.

Genetics, too, can play a part in the strength of your memories. ‘Genetic factors affect how efficiently the brain generates synaptic growth and this varies between people,’ says Professor Logie.

But it also depends what happens during encoding — the period between the event happening and the memory being stored with multiple synapse connections. The time lag between a memorable event happening and it being encoded varies.

‘The initial encoding will take place in seconds, but the more long-term encoding takes a day or a good night’s sleep,’ says Professor Mellor.

‘All memories need to be consolidated to be fixed for the long term and we are finding more and more that sleep is important in making that happen.’

However, not all consolidation takes place during sleep — some happens while we are awake.

‘If you take people who had a head injury who were knocked out playing rugby, for example — quite often they can’t remember what happened just before they were knocked out because the synaptic growth and consolidation hadn’t yet taken place before they had the injury,’ says Professor Logie.

‘But that’s also why if you have a busy day multi-tasking, you might be forgetful. You aren’t giving your brain a chance to consolidate memories.’

Stress, too, can have a big impact on your memory forming.

A review of 113 studies from the University of California found that if people were stressed during encoding, this impaired the formation of memory. But a short burst of stress can enhance the encoding, they reported in the journal Psychological Bulletin in 2017.

Sleep, however, also seems to be crucial to what happens after encoding, an area at the cutting edge of research.

‘One interesting idea is that in the hippocampus [an area deep in the mid-brain connected to memory], you have the short-term memory formed during the day and during sleep, that’s shifted into the outside of the brain, the cortex,’ says Professor Mellor.

This highly sophisticated filing system may go toward explaining why we never seem to run out of memory space.

‘In terms of fitting in more knowledge — we seem to have unlimited capacity,’ says Professor Bird. However, the brain has a priority function to determine which memories to give prominence to. As Professor Mellor explains: ‘We think that if it comes with emotional importance — if something makes you feel really good or bad — that has a signal associated with it which tells those synapses to be reactivated during sleep.’ What helps alert the brain to which memories to prioritise is the release of certain chemicals associated with the memories at the time they are formed — such as feelgood chemicals dopamine or serotonin or, at the other end of the emotional spectrum, adrenaline.

In other words, if something makes you feel great or scared or very happy, the more chance you will remember that than something more run of the mill.

But some memories aren’t designed to be preserved. Unlike long-term memories, your working memories — the type of memory that helps you tot up figures in your head or that takes account of traffic behind us as we go to overtake on a motorway, for example — is more fleeting.

‘It allows us to keep track around us as things are changing and we tend not to encode all of that,’ says Professor Logie. In fact, the ability to forget certain things is in many ways useful, he says.

‘Forgetting is a human superpower. It’s why our brains are actually superior to a computer, which doesn’t have that capacity.

‘Letting go of all the trivial details of our experience — the shape of the apple we have been eating, the colour of the car we overtook — stops our memory getting too cluttered with useless trivia,’ he says.

This is important for that moment when you try to recall an event, which is when your brain is in effect conducting a Google search. ‘That’s the easiest way to put it,’ says Professor Bird. ‘And often, just as with Google searches, it throws up lots of answers’ — and piecing together which is the right one isn’t a perfect process.

‘One thing we now know is that it [memory recall] doesn’t work like a video recorder, where you press record and then play and get it back,’ he adds.

‘It’s a much more complex process — you have to put together what you think happened. That’s why you may remember something differently to how it actually happened. As we remember things again and again, the memory becomes more robust,’ he says.

How to make memories more robust is an area of scientific interest.

While there is much more research to be done on this, those wanting to improve their memory in the meantime could do worse than get enough sleep — and take exercise.

Various studies have found that aerobic exercise, such as running, walking and swimming, can improve memory — with one review published in Nature this year finding that it is particularly beneficial for the over-55s.

The authors looked at 36 studies involving almost 3,000 people and concluded that ‘aerobic exercise is an accessible, non-pharmaceutical intervention to improve episodic memory late in adulthood’. ‘Exercise helps oxygen flow round the body to the brain — it needs oxygen to thrive — and exercise protects against health issues that may impact on your memory,’ says Professor Logie.

He takes a less energetic approach to memory. ‘I try to learn as much as I can,’ he adds, explaining the more memories you have on a certain subject the easier it is to bring that ‘file’ to mind.

But he also keeps his attention on one task followed by another: ‘I try to focus on one thing at a time rather than multitasking, as this allows you to consolidate — and for me it works,’ he says.

What bees that play football could teach us about recall

How to make memories more robust is an area of huge scientific interest — with bees providing surprising insights.

‘Bees are useful models of how much intelligence you can squeeze into a small brain,’ says Lars Chittka, a professor of sensory and behavioural ecology from Queen Mary University of London.

He co-authored a seminal study, published last November in Nature Communications, which showed how the gut bacteria of bees can influence the strength of their memories.

‘Their brains are about the size of a pinhead and while we have 85 billion neurons [nerve cells] in ours, bees have less than a million, so using bees means we can tackle questions about memory in a less complex system,’ he says.

Bees memorise a lot on a daily basis, he adds. ‘They have a home whose location they have to memorise — they can fly up to 10 km [six miles] away and have to be able to reliably find their way back home because they can’t live on their own. They would die.

‘When we tested them in the lab, it turns out they can memorise human faces, points of interest and learn to count’ — counting landmarks to locate their hive — as well as learning and memorising skills. This included teaching the bees to play football. They had to move a pea-sized ball to a goal by ‘kicking’ it, getting a drop of nectar if they scored.

‘They could also learn how to do this by observing each other,’ says Professor Chittka.

After seeing initial studies suggesting gut bacteria may be implicated in memory, Professor Chittka decided to investigate this in bees. The team set up ten different-coloured flowers in the lab. Five contained a nectar ‘reward’ and five didn’t; the bees were able to fly between them.

The assumption was that the bees would recall the flowers with nectar. The insects were then tested up to three days later to see if they could remember which flower was which. The results were correlated with their gut bacteria.

Next, one group’s diet was supplemented with Lactobacillus apis, a bacteria also found in the human gut that they identified as being linked to better memory. A control group had none.

‘It was astonishing,’ says Professor Chittka. ‘With supplementation, there was a 20 to 25 per cent enhancement in their ability to recall the flowers with the nectar reward.

‘One theory is that the bacteria increased levels of glycerophospholipids — a form of fat ‘known in bees and humans to be important building blocks in neural membranes.

‘These were elevated in the bees’ blood, so might be useful in building neurons and connections between them.’

The next step is to try the work in rats and then humans.

‘The dream would be to provide supplements that would benefit human memory, especially in those with degenerative disease,’ he says.

It’s not the only study linking the microbiome and memory. A study by the University of Georgia in the journal Translational Psychiatry last year, found that having sugary drinks as an adolescent has a negative impact on memory in adulthood. It’s thought the sugar affects the make-up of the microbiome.

Source: Read Full Article