A new study on culture and cognition found that long-term Hispanic immigrants who were less acculturated to the U.S. performed significantly worse on cognitive function tests than their highly acculturated peers.

A team of researchers led by scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign assessed the acculturation levels and cognitive function of more than 600 Hispanics age 60 or older who were born in or had immigrated to the U.S.

Their acculturation level was assessed using two measures—nativity status, which included place of birth and length of residence in the U.S.; and language acculturation, which documented whether participants were bilingual or spoke primarily Spanish or English at home.

Hispanic older adults in the study who spoke only or mostly English at home and were born in the U.S. were considered highly acculturated, while immigrants born in other countries and had lived in the U.S. less than 15 years, were bilingual or spoke primarily Spanish at home were considered to be less acculturated.

“Our study confirms the existence of within-group health and sociocultural disparities that are dependent on the degree of acculturation,” said Rifat B. Alam, a graduate student at the U. of I. and first author of the research. “Our findings suggest that low acculturation in terms of both nativity status and language acculturation is associated with lower scores on cognitive performance tests. The study also underscores the complex effects of cultural factors in the development of dementia.”

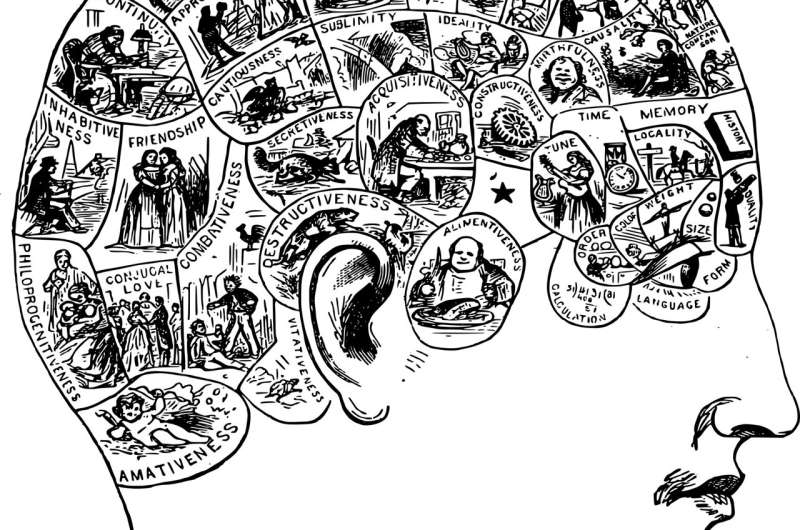

Participants’ cognitive performance was measured with two commonly used neuropsychological tests: The Animal Fluency Test, which assesses verbal semantic fluency, a component of executive functioning, by asking participants to recall as many animals as they can within one minute; and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, a written test that measures attention processing and working memory by having test-takers match a set of symbols to a row of numbers within a two-minute period.

The AFT can detect mild to severe forms of cognitive impairment while the DSST measures test-takers’ ability to perform everyday activities, skills that are impaired in people with dementia and other mental diseases, according to the study.

“In the crude models, participants’ scores on these tests were significantly associated with nativity status and language acculturation,” Alam said. “After controlling for sociodemographic and health factors, we found that Hispanics who had low levels of acculturation on both nativity status and language showed poorer cognitive performance than their highly acculturated U.S.-born peers.”

Hispanics’ risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease is 1.5 times greater than that of non-Hispanic whites in the U.S. Some prior research has attributed this disparity to a greater incidence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and lifestyle factors such as tobacco use and consumption of junk food—factors that also have been associated with high acculturation.

However, in other studies, high acculturation was associated with greater levels of protective factors such as increased physical activity, health insurance and health care utilization.

“The role of acculturation is an important factor in the cognitive health of racially and ethnically underrepresented groups that should be explored further,” said kinesiology and community health professor and co-author Andiara Schwingel. “The migration experiences—including age at arrival and reasons for migration, socioeconomic disadvantage, social support and bilingualism—all appear to be important factors that impact cognition.”

“Our research underscores the importance of cultural factors in dementia development and the need for culturally sensitive low-cost programs for Hispanics to mitigate health disparities and address challenges in health practices, such as prioritizing of groups seeking dementia treatment,” Schwingel said.

Source: Read Full Article