- Researchers investigated the effects of exercise on inflammation in mice.

- They found that regular moderate exercise reduces inflammatory markers in mice.

- This was due to epigenetic changes that affected the expression of genes responsible for the inflammatory responses of certain immune cells.

- Further studies are needed to see if these findings translate to humans.

Inflammation happens when the body’s immune system has a reaction. This could be to pathogens such as germs, foreign bodies, and anything else the immune system recognizes as foreign.

While it can be crucial for restoring tissue and healing, excessive and chronic inflammation can result in conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disease.

Studies have shown that exercise can modulate the immune system. Research shows that moderate-intensity exercise exerts anti-inflammatory effects. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain how exercise exerts these effects, including decreased fat mass and altered function of immune cells known as macrophages.

How exactly exercise induces these changes that reduce inflammation, however, remains unknown. Further research on how this happens could inform treatment and prevention options for inflammation-related health conditions.

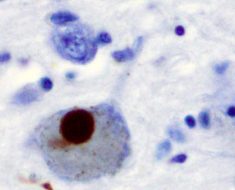

Recently, researchers explored how macrophages present in bone marrow changed following exercise to induce anti-inflammatory effects.

They found that regular moderate exercise reduces the inflammatory response by rewiring metabolic and epigenetic function in macrophages.

Dr. Ali Abdul-Sater, associate professor of immunology and physiology at York University, Canada, one of the study’s authors, told Medical News Today:

“Obviously, different people would require different exercise programs after factoring in their specific condition. However, overall, I think that what this tells us is that engaging in moderate and regular exercise will likely ‘educate’”’ the immune cells in active individuals so they have a more balanced inflammatory response when they are exposed to an infection or injury.”

The study was published in Cell Physiology.

Effects of exercise on mitochondrial function

For the study, the researchers gathered female mice and split them into two groups: one that exercised on a treadmill for one hour per day, and the other that did not exercise at all. Both exercise regimes lasted for eight weeks.

The researchers collected bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from both groups of mice and conducted various tests to assess their inflammatory and antiviral responses.

Ultimately, they found that gene expression of inflammatory genes in exercised mice’s BMDM’s was significantly lower than that in sedentary controls, due to changes in the accessibility of those genes for transcription.

The researchers also noted that exercise inhibited other pathways linked to inflammation compared to controls.

To understand why this may be the case, the researchers examined the effects of exercise on mitochondrial function in the BMDMs. Mitochondria play a significant role in metabolic processes that control inflammation and macrophage activation.

They found that moderate exercise reduced oxidative stress in BMDMs, and improved overall mitochondrial quality in BMDMs. These improvements, they noted, occurred similarly to how mitochondria adapt in muscle cells following exercise.

The researchers next wanted to see whether these effects could be maintained long-term. To do so, they examined BMDM’s from exercised mice after they stopped exercised. After exercise was stopped for two weeks, both oxidative stress and mitochondrial potential reduced to sedentary levels.

How inflammation may lead to obesity

Dr.Isabelle Amigues, a rheumatology specialist in Denver, CO, not involved in the study, told MNT:

“Overweight and obesity are well known causes of pro-inflammatory states. Any prolonged inflammatory state can cause dysfunction in the immune system. For example, being overweight and obese is a known risk factor to develop psoriatic arthritis or cancer.”

Dr. Jacob Teitelbaum, a board certified internist not involved in the study, told MNT that inflammation may also increase the risk of weight gain.

“Normally, acute infections like pneumonias […] increase the burning of fat cells for energy, causing weight loss,” Dr. Teitelbaum explained.

“But, after these infections and inflammation become chronic, as is seen in postinfectious and other causes of chronic fatigue syndrome such as long COVID, a number of changes cause weight gain to occur.”

“Two of our in house studies showed an average 32 ½ pound weight gain in people with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. We can expect to see this starting to show itself over the coming years as one more devastating effect of Long COVID,” Dr. Teitelbaum added.

When asked how inflammation may increase weight gain, Dr. Teitelbaum noted many possible causes. Among them, he said that inflammation may increase the production of the stress hormone cortisol, which causes insulin resistance and weight gain.

“[Weight gain may also occur if the body attempts] to conserve energy in the face of inflammation, resulting in what is called T3 thyroid receptor resistance. Basically, the body becomes deaf to thyroid hormone, suppressing metabolism, and causing hypothyroidism, [which is linked to weight increase largely through salt and water retention] despite normal lab tests.”

— Dr. Jacob Teitelbaum, internist

Inflammatory pathways

MNT also spoke with Dr. Tejasav Sehrawat, resident physician of internal medicine at Yale University School of Medicine, not involved in the study.

“The pathway the authors elegantly describe in this study, is the same pathway that when targeted against causes of fatty liver disease in our studies at Mayo Clinic helped treat the condition,” Dr. Sehrawat said.

“It is also the same pathway that is triggered by alcohol misuse and the damage that is further inflicted in the body. This goes to show the far-reaching implications of understanding and further developing these concepts we can try to effectively target chronic inflammatory diseases,” he added.

Limitations of mouse models

When asked about the study’s limitations, Dr. Teitelbaum said the study only observed a “small area of the body-wide response to exercise,” and noted the findings were based on mice rather than humans.

“Granted, the mouse’s immune system is closely related to humans, but the way they were exercised in cages is not that reflective of human experience,” Dr. Teitelbaum said.

“Basically, they were looking at one very small piece of a very big puzzle. While important to do, it’s important to keep perspective as well.”

MNT also spoke with Ryan Glatt, senior brain health coach and director of the FitBrain Program at Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica, CA, not involved in the study.

Glad noted another limitation is there are “many inflammatory biomarkers and myokines that can be measured, so it is very difficult to get a complete picture of how they all play a role.”

Other ways to reduce inflammation

Glatt said the biggest takeaway from the study “seems to be that exercise can yield anti-inflammatory effects through the upregulation of anti-inflammatory biomarkers and the decrease of pro-inflammatory biomarkers.”

When asked how to put these findings into action, Dr. Teitelbaum said:

“Simple lifestyle modifications, including exercise in the sunshine, can have massive health benefits. These can include a healthier and balanced immune system, weight loss, and a decreased tendency to diabetes and heart disease — not to mention decreased anxiety and depression. Go for walks in the sunshine […], and exercise nutritional common sense. These simple measures can leave you healthier, happier, slimmer, and with a balanced immune system.”

Of course, adhering to a healthy, balanced diet that emphasizes whole foods and limits or avoids processed foods and excess sugar may also help lower inflammation. Increasing omega-3 fatty acid intake may also be beneficial, Dr. Teitelbaum concluded.

Source: Read Full Article