Researchers have found that there are substantial differences in who was asked to shield from coronavirus depending on where they live in the UK.

Differences in age, methods of identifying those at risk, and the proportion of shielding people who live in deprived areas were the main findings from the first wave of data to come out of the project. This the researchers suggest, means that a one-size-fits-all care plan to support these vulnerable people will not be effective and highlights the need for tailored guidance and support.

This is the first update from the Health Foundation’s Networked Data Lab (NDL) a new collaboration of researchers from across the UK who are analyzing NHS data to help inform important health and care decisions. Scientists from both the University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian form the Scottish arm of the NDL. The full report can be accessed here.

The first project for the team has been to study those who were told to shield from coronavirus because they were identified as vulnerable to severe illness if they were to be infected. In March 2020, the NHS identified people who, due to underlying health conditions, could be at especially high risk from COVID-19. These people were then directed to stay at home and minimize contact with people outside their household with the aim being to reduce the risk of infection and the severe health consequences of COVID-19.

Dr. Jessica Butler, Research Fellow at the University and Analytical Lead for the project in Grampian, explains: “The shielding plan was made to protect those at very high risk of serious health problems if they contracted COVID-19. However, shielding could also have far-reaching negative consequences.

“Shielding could result in people not receiving usual healthcare for their underlying conditions so isolation now may result in worse outcomes and heavier use of healthcare later which means there is an urgent need to understand and plan for the healthcare needs of those shielding.

“It is our view that careful monitoring and early intervention are key to lowering risk. Sharing and understanding the range of local approaches used to identify the most vulnerable and support them helps to ensure that all who are at risk are identified and given equitable access to the services they need,” says Dr. Jessica Butler, Research Fellow at the University and Analytical Lead for the project in Grampian.

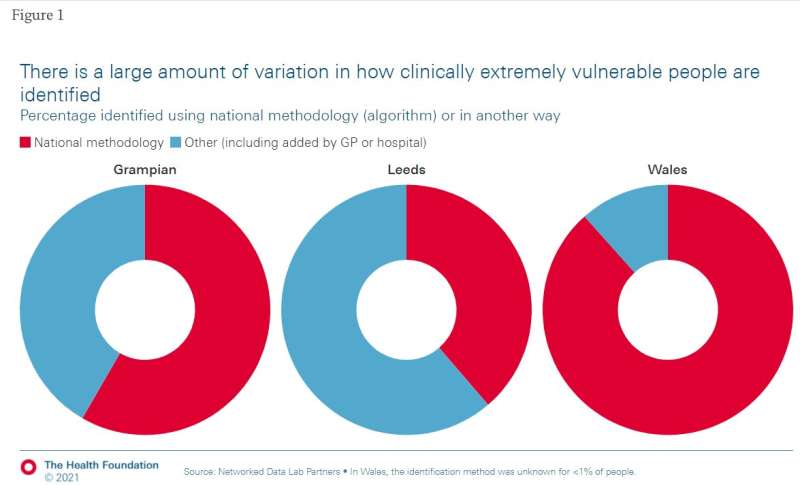

In their analysis of the shielding population, the team found that there were differences in how many people were asked to shield according to where they lived. Grampian had the lowest proportion of the population asked to shield with only 2.5% (about 15,000 people), compared to 4.2% in Wales, 5.1% in North West London, 5.3% in Leeds and 7.5% in Liverpool and Wirral. There were also differences in how shielders were identified, for example, in Wales the majority of people asked to shield were identified by automated scan of their medical records, while in Grampian many people were asked because their GP or hospital consultant believed they were vulnerable to COVID-19.

The team also found that those asked to shield were a very diverse group of people, both in terms of their personal characteristics and in their underlying medical conditions. Those asked to shield in Grampian were much older than the population average, and more likely to live in an area that the Scottish Government classifies as deprived. However, in total in Grampian, only 8% of the clinically extremely vulnerable population live in the most deprived areas, compared with 60% of people shielding in Liverpool and Wirral. In Grampian the main reason people were asked to shield was having an underlying respiratory illness like COPD or severe asthma, followed by use of immunosuppressants and cancer.

Dr. Butler explains further: “We found substantial variation across the UK in how shielders were identified as well as in their personal circumstances—including the types of illnesses they have, where they live whether that’s in towns and cities or rurally, neighborhood deprivation, and ethnicity, all of which highlights the different types of support that will be needed to ensure this diverse group can stay safe.

“Most importantly, sharing and understanding the range of local approaches used to identify the most vulnerable and support them helps to ensure that all who are at risk are identified and given equitable access to the services they need.

Source: Read Full Article