Nearly five million people in the United States are living with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, which causes life-changing memory loss. And with the prevalence of the disease expected to double by 2060, it’s worth asking, “Is there a test for Alzheimer’s?”

A new study found that higher blood levels of a protein called neurofilament light chain (NfL) correlated with the onset of symptoms in people with a genetic form of Alzheimer’s disease. The greater the levels of NfL at the start of the study, the more likely a person was to experience memory and cognitive decline 16 years later.

“We know [Alzheimer’s] in the brain begins 10 to 20 years before symptoms emerge,” Mathias Jucker, Ph.D., senior investigator and a professor at the Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Germany, told ABC News. He said the findings were “helpful” in advancing Alzheimer’s research.

Still, this doesn’t mean that the test itself detects Alzheimer’s, according to Brian Gordon, Ph.D., co-author of the study and an assistant professor of radiology at Washington University in St. Louis, told ABC News.

Why isn’t it a reliable test for Alzheimer’s? Let’s break it down.

It’s still unknown what causes Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is formally diagnosed with tests that assess memory and thinking impairment, which are administered by medical doctors and trained clinicians. Alzheimer’s may result from a combination of environmental, lifestyle and genetic risk. Genetically inherited Alzheimer’s, which is the kind that the new study examined, accounts for less than 1 percent cases.

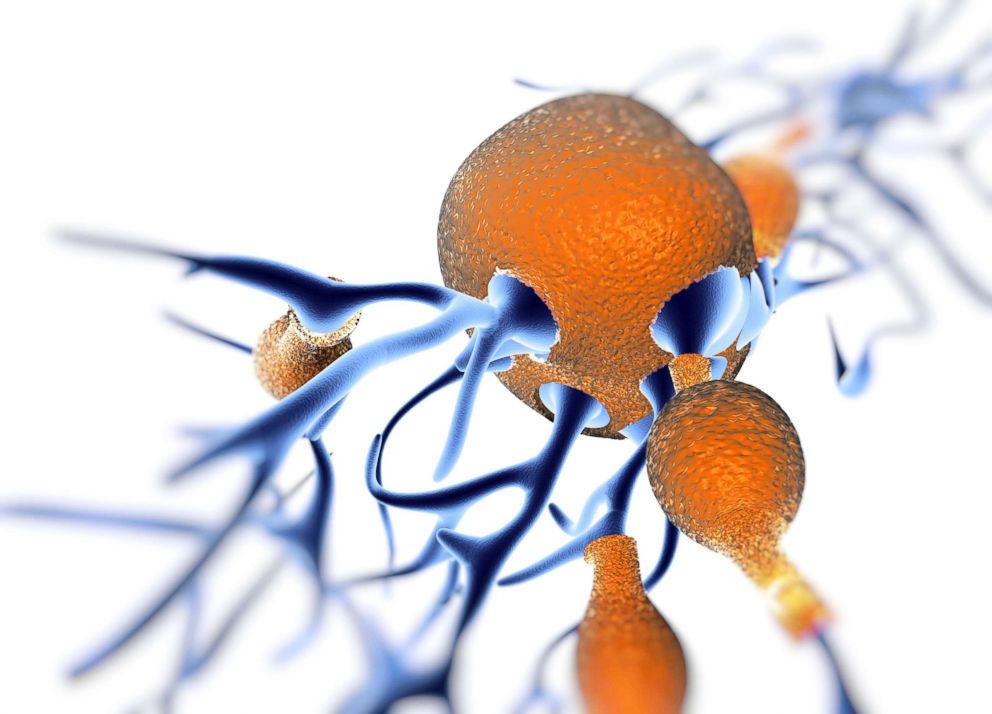

The build-up of protein tangles and plaques — namely tau and amyloid — in the brain have been associated with brain cell damage in Alzheimer’s. However, the role they play in causing Alzheimer’s is still unclear. Early stage trials that target amyloid are underway.

Some research suggests bacteria associated with poor oral hygiene and an imbalanced microbiome due to a poor diet may play a role. This oral bacteria and its toxin have been found in brains with Alzheimer’s disease.

One study, for example, looked at how an infection from this bacteria affected animals and human brain samples, and found that the infection led to Alzheimer’s symptoms and brain damage. Specifically, the study found that the number of bacteria in human brain tissue correlated with the number of tau proteins. In the animals, it found that the number of bacteria was linked to an increased production of amyloid proteins. When the animals were treated for the infection, the researchers saw their symptoms improve. Further research is necessary to test this evidence in human clinical trials.

A blood test is not yet able to predict Alzheimer’s.

NfL is not specific to Alzheimer’s and is seen in higher levels in people with other conditions, including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders, brain bleeds and even in neurologic complications of HIV.

“It seems like every couple months a new study comes out showing that NfL is sensitive to brain damage in another new condition,” Gordon said. “The test is picking up damage in the brain tied to [Alzheimer’s] in our particular [study], but it would also pick up damage tied to many other diseases in other [individuals]. Some of the media outlets have missed that point.”

It would, therefore, be challenging to interpret what an elevated NfL level means, especially in those with other medical issues.

Furthermore, this study only included individuals with only genetically inherited Alzheimer’s disease. A 2017 study that included non-genetic Alzheimer’s types concluded that blood NfL levels “may not be a useful biomarker for the diagnosis of prodromal and dementia stages of [Alzheimer’s].”

So, what is this NfL test good for then? According to Dr. Randall Bateman, co-author of the study from the Department of Neurology at Washington University, NfL levels may be considered in standard tests for tracking the progression of brain damage once there is a treatment for Alzheimer’s.

Despite the unknowns of Alzheimer’s, there are steps you can take to protect your brain.

Dementia may be partially preventable and is often linked to cardiovascular health. You can optimize your brain health by getting adequate physical activity; consuming a healthy diet, low in saturated fat and high in fiber; getting good sleep; maintaining good oral hygiene; having good social support around you; always challenging your brain by learning new things and avoiding head trauma.

While there are still lots of unknowns with regard to Alzheimer’s, Dr. James Pickett of the Alzheimer’s Society acknowledged the importance of this research, telling The Guardian that “any progress we can make to more accurately and quickly detect who has the condition is very welcome.”

Dr. Robin Ortiz is a physician in internal medicine and pediatrics and a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.

Source: Read Full Article