Those who struggle to understand someone giving an excited, rapid-fire account of an adventure, or who lose the thread of a conversation during a noisy cocktail party might be dealing with problems detecting rapid changes in sound—and new University of Maryland research could help.

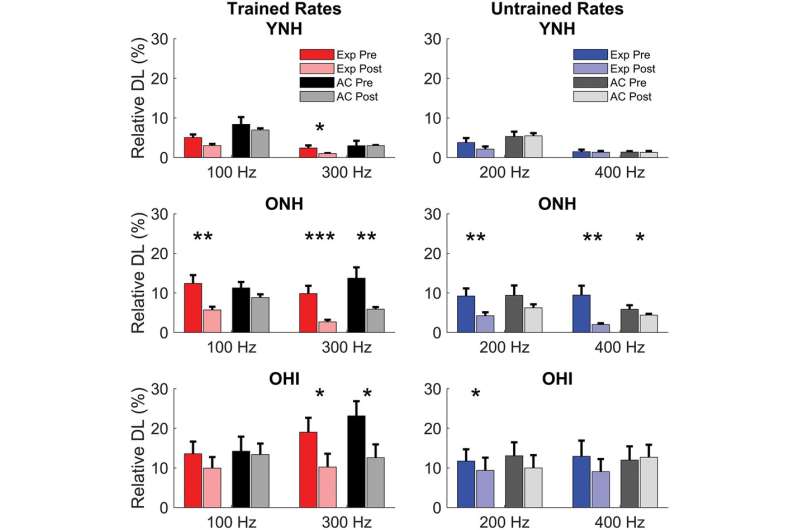

In a recent study published in the Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, researchers in the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences found that people aged 18–30 and 65–85 with normal hearing—as well as participants from the older age group with hearing impairment—could all be trained to boost their ability to differentiate subtle changes in the speed, or “rate,” of sounds. Such changes can make it difficult to understand speech in challenging situations, such as in noisy or reverberant environments, or when listening to people who talk fast.

“We’ve seen some evidence that these temporal processing deficits might be improved in animal models, but this is the first time we’ve shown it in humans,” said Associate Professor Samira Anderson, the publication’s lead author. Her co-authors include Professors Matthew Goupell and Sandra Gordon-Salant.

For the training, participants in the 40-person experimental group compared multiple series of rapid tones (think beeps or clicks) in nine sessions over three weeks. Compared to members of the 37-person control group, who were asked to detect a single tone, those in the experimental group showed overall improvement. Most significantly, older normal-hearing people who undergo training can essentially restore their ability to discriminate fast changes in the timing of sounds to levels similar to those observed for young adults.

This rate discrimination study is one of three UMD projects. Gordon-Salant, director of the UMD Hearing Research Lab, is principal investigator for the projects. Each seeks to examine how the aging brain contributes to auditory and speech perception difficulties, and ultimately whether targeted auditory and cognitive training can help restore effective auditory processing—with distinctly different approaches.

The rate discrimination study is the first to show that “auditory training promotes neural changes in the brain, known as neuroplasticity,” Gordon-Salant said. “The results offer great hope in developing clinically feasible auditory training programs that can improve older listeners’ ability to communicate in difficult situations.”

Gordon-Salant and colleagues are actively recruiting individuals who have normal hearing or mild-to-moderate hearing loss to participate in the next phase of this rate discrimination study, as well as the other neuroplasticity study on whether memory demands impact the effectiveness of humans’ training program. The third project, which focuses on aging animals’ ability to hear sounds amid noise, is led by Shihab Shamma of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Institute for Systems Research.

More information:

Samira Anderson et al, Rate Discrimination Training May Partially Restore Temporal Processing Abilities from Age-Related Deficits, Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s10162-022-00859-x

Journal information:

Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology

Source: Read Full Article