The question is, why didn’t we think of this before? Most of us own inkjet printers, yet few of us, except one, have every thought of doing anything else with a printer except print documents. Except Dr. Thomas Boland, who thought of something else.

In the early 2000s, bioengineer Dr. Thomas Boland, retrofitted a standard inkjet printer so that it would use cells as ink. By 2003 he had started to develop “organ printers” with the concept that a desktop printer could print gels, single cells, and aggregates of cells in a sequential layer-by-layer manner so that organs could be printed and assembled as if for the first time. He was onto something.

More than 10 years later, 3-dimensional (3-D) printing and bio-printing are a reality and will be even more commonplace as the years go by. In a report released by Goldman Sachs last year, 3-D printing is already a $2.2 billion market; analysts estimate that the industry will grow to more than $10 billion by 2021. Although it makes up less than 20% of the current market, the 3-D printing industry, many believe, has the potential to revolutionize many aspects of health care.

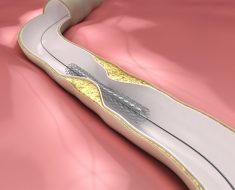

Much of the interest about biomedical applications of 3-D printing is its ability to recreate objects that have precise sizes, contours, and measurements. For example, radiographic data can be used to create segments of missing bone for trauma patients, teeth can be perfectly printed for those who need dental implants, and prosthetic eyes can be printed in a matter of minutes. And for women, these ideas have been applied in the most needful ways.

Laura Bosworth wants to 3D print breast nipples on demand. The CEO of the Texas startup TeVido Biodevices is hopeful that survivors of breast cancer who have undergone mastectomies will be able acquire new breasts printed from their own living cells.

“Everyone,” she says, “knows a woman who has had breast cancer.” Right now their options are limited. Reconstructed nipples using state-of-the-art plastic surgery techniques, she says, “tend to flatten and fade and don’t last very long.” A living nipple built from the patient’s own fat cells, and reconstructed to the precise specification of the original nipple, could help minimize the psychological pain often associated with mastectomies.

Further, one company in Bavaria is helping women who have had breast surgery through the customization possibilities offered by 3D printing. Lingerie company Anita has employed their German RepRap X400 to streamline the making of breast prostheses. The 3D printing processes have saved about 50% of their cost to make these specialized products.

Partial and full mastectomies can lead to asymmetry, postural imbalance, and a fragmented body image. Anita is working to restore confidence, and more positive body image, after surgery.

Source: Read Full Article