Mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles are well known as primary vectors of malaria. But a new study suggests that Anopheles species, including some found in the United States, also are capable of carrying and transmitting an emerging pathogen, Mayaro virus, which has caused outbreaks of disease in South America and the Caribbean.

Mayaro virus—which can cause fever, joint aches, muscle pains, headache, eye pain, rash, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea—first was isolated from the blood of five symptomatic workers in Mayaro County, Trinidad, in 1954. Since then, it has caused sporadic outbreaks and small epidemics in several South and Central American countries.

In addition, imported cases may be on the rise, with several reported recently in the Netherlands, Germany, France and Switzerland, according to researchers.

“Because the symptoms of Mayaro infection are similar to those caused by other arboviruses [arthropod-borne virus] such as dengue and chikungunya, its prevalence in areas where these other viruses circulate may be higher than reported,” said the study’s senior author, Jason Rasgon, professor of entomology and disease epidemiology, College of Agricultural Sciences, Penn State.

Rasgon explained that Mayaro virus is thought to be transmitted primarily by canopy-dwelling mosquitoes of the genus Haemagogus. Human infections are sporadic, he said, because Haemagogus species tend to live in rural areas in proximity to forests—where they cycle the virus among nonhuman primates and birds—and do not typically prefer to feed on people. However, when the virus is introduced into urban areas, other mosquito species potentially could trigger epidemics in human populations.

“With the recent increase in imported cases, there are invasion concerns similar to those associated with Zika and chikungunya viruses,” Rasgon said. “But little is known about the range of mosquito species that are capable vectors of Mayaro, so our aim was to address that knowledge gap.”

In this study, the researchers tested six mosquito species—Aedes aegypti, Anopheles freeborni, An. gambiae, An. quadrimaculatus, An. stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus—for their ability to transmit two strains of the Mayaro virus. The four Anopheles species were selected to cover different geographical regions: North America (An. freeborni and An. quadrimaculatus), Africa (An. gambiae) and Southeast Asia (An. stephensi).

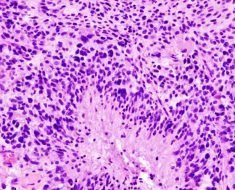

Mosquitoes were allowed to feed on human blood spiked with the virus via a glass feeder. Researchers then assessed each species at seven and 14 days after infection to determine infection rate (rate of mosquitoes with infected bodies among those analyzed), dissemination rate (rate of mosquitoes with infected legs among those with positive bodies), transmission rate (rate of mosquitoes with infectious saliva among those with positive legs), and transmission efficiency (rate of mosquitoes with infectious saliva among the total number analyzed).

They found that Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus were poor vectors of Mayaro virus, with either poor or null infection and transmission rates. However, the results, reported today (Nov. 7) in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, demonstrated that all four Anopheles species were competent laboratory vectors of the virus.

“The capacity of the two North American species of Anopheles to transmit Mayaro is particularly relevant to the United States, because the estimated geographic distribution of these species covers the entire country,” Rasgon said.

“The transmission cycle of Mayaro involves mostly nonhuman primates and birds, although there is some evidence of circulation in rodents and marsupials,” he said. “We don’t know about the capacity of North American mammal species to act as vertebrate reservoirs, but it’s possible that Mayaro virus could be maintained in a human-mosquito-human urban cycle similar to what we’ve seen with chikungunya.”

In addition, the researchers noted, Anopheles mosquitoes tend to take multiple blood meals between egg-laying events, and this bite frequency increases their capacity to transmit viruses.

Source: Read Full Article