Mucus and other airway secretions that are expelled when a person with the flu coughs or exhales appear to protect the virus when it becomes airborne, regardless of humidity levels, a creative experiment conducted by the University of Pittsburgh and Virginia Tech discovered.

The results, published in today’s issue of the Journal of Infectious Diseases, refute long-standing studies that indicated the influenza virus degrades and is inactivated sooner as the humidity increases.

“Our findings highlight the importance of mimicking real-world conditions when determining the infectivity of emerging viruses,” said Seema S. Lakdawala, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Pitt School of Medicine’s Department of Microbiology & Molecular Genetics. “This has critical implications when public health organizations devise ways to stem the spread of infections, particularly during pandemics.”

Influenza viruses emerge every winter in temperate regions when people are in closer contact inside, better enabling person-to-person spread. But it is also much less humid inside buildings that are heated in winter, and previous experiments using aerosolized flu virus alone—not in combination with airway secretions—showed that moderate to high humidity inactivated the virus. So it was assumed that dry winter air had a protective effect that also allowed the flu virus to thrive.

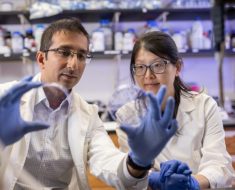

Lakdawala partnered with Linsey C. Marr, Ph.D., of Virginia Tech’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, to put that assumption to the test. They devised a way to artificially create real-world conditions to test how long the influenza virus, when expelled by someone with the flu, would be expected to survive in a typical indoor setting under a variety of different relative humidity levels.

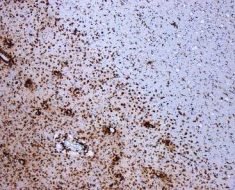

Marr’s research team, including Virginia Tech graduate student Kaisen Lin, M.S., designed a rotating metal drum that keeps aerosols suspended while maintaining a constant relative humidity level. Lakdawala’s team combined samples of human airway secretions with the 2009 pandemic H1N1 flu strain, aerosolized the mixture and sprayed it into the drum—similar to what would be expected to be emitted into a room from someone who is sick. The drum was fitted with special filters to prevent the release of the virus, and the entire experiment was run inside a biosafety cabinet.

The team ran the drum for an hour—a typical length of time that air stays in homes and other buildings before moving outside—at seven different humidity levels, representative of dry climates and heated indoor environments in winter, indoor environments during warmer seasons, and rainy and tropical climates.

Karen Kormuth, Ph.D., a post-doctoral associate in Lakdawala’s laboratory, analyzed the results from the drum experiment and showed them to Lakdawala.

“I was astonished,” said Lakdawala. “The flu virus remained just as infectious at all humidity levels. The airway secretions were protecting it for at least the length of time it would take a typical home to exchange most of its air.”

“The result was surprising,” Marr added, “because our previous work suggested that the flu virus survived better at low humidity. We thought this might help explain why flu season occurs in the winter, when humidity is low indoors, but we now have to rethink what’s happening with the virus when it’s in droplets and aerosols.”

The team stresses that the immediate take-away from their study is that, during flu season, homes and offices should employ a combination of increased air exchange rates coupled with filtration or UV irradiation of recirculated air, as well as regular disinfection of high-touch surfaces, such as door knobs, keyboards, phones and desks.

Future research should involve testing other strains of flu and different pathogens to learn if they, too, are protected by airway secretions when airborne.

Source: Read Full Article