To prove that a medical treatment works, scientists must run not just one human trial but several. This poses a challenge that many scientists aren’t formally trained to tackle: Recruit hundreds of participants through elaborate marketing and networking.

A research lab at the University of Texas at Dallas can attest to that.

The lab, led by Professor John Hart Jr., is testing a brain-stimulating device that could help people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. The device uses repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or rTMS, to work with therapy to further reduce PTSD symptoms.

The lab has already proven that rTMS is effective for PTSD when coupled with therapy in a past human trial, with the results published last year in the Journal of Affective Disorders. Funded by the Department of Defense, the researchers tested the treatment on 100 veterans with combat-related PTSD.

Their next step? Test it again with over 300 veterans “just to confirm that it has positive effects,” says Khadija Saifullah, a graduate student of neuroscience who works in the lab.

For the next five years, the researchers will be recruiting participants for this replication trial from three sites: UT Dallas, Metrocare Services in Dallas and the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Fla.

Combat veterans are especially affected by PTSD. As many as a fifth of veterans who served in the post-9/11 Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts suffer from PTSD in any given year, says the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The rTMS device was already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat depression over a decade ago and is currently used at many Veterans Affairs hospitals for this. “We’re just using it for a slightly different mental health issue,” says Saifullah.

Most people have gone through some sort of trauma in their life. For the millions of Americans who suffer from PTSD, though, the memories of the event have debilitated them. They suffer from flashbacks, nightmares and enhanced fear triggered by sounds, sights or smells that pull them back into their haunting past.

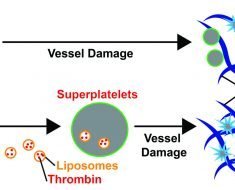

The device works as a temporary stimulator for part of the brain. The researchers position the rTMS coil, which is shaped like Mickey Mouse ears, over the patient’s head. For about 30 minutes, the device gives off subtle magnetic pulses that are believed to “interrupt fight/flight/freeze stress response,” says Kelsey Watson, a psychology researcher who works in the lab.

The emotion-suppressing effects of a single rTMS session only lasts for about an hour. Patients promptly attend a typical therapy session after with the goal that they can discuss their traumatic experiences without the emotional part of their brain insisting on an anxiety overcharge. Continued rTMS sessions over time may subdue PTSD-related anxiety for even longer time periods.

The lab just started searching for patients to participate in their replication trial a little over two months ago.

The lab’s recruitment is off to a good start, but “I liken it to pushing a snowball up a hill,” Watson says. “We have this small thing of snow, and that’s our study. We’re so excited about it, but only the people in our lab know about it.”

The snowball grows larger as the research team informs colleges, veteran organizations, and local businesses about the new trial. But pushing the snowball up that hill to accrue these connections requires consistent work.

“There’s not a PTSD hotline, chat room or society that you can go to and say, ‘Everybody, here’s the thing!’ and they’ll say, ‘Oh my gosh, look at this thing!’,” says Hart. What’s more, the prospective participant must meet qualifications that accompany any human study.

So Watson and the other lab members must be constantly attending different events, meeting community leaders, telling Texas about their research efforts on social media and through radio and podcast interviews.

“I’m a clinical psychology student,” says Watson. “I did not do marketing. I did not do data management.” For her, it’s been “the crash course in ‘Let’s get this out there.’ “

Scientists all across the U.S. are finding themselves in that same course, says Dr. Joyce Chung, the deputy clinical director at the National Institute of Mental Health, or NIMH.

“This is not what you learn in medical school or graduate school—how to recruit participants,” says Chung, who is not involved in the UTD research efforts. “It’s definitely something you learn as you’re going along, and you realize how important that is.”

Old-fashioned marketing such as bus ads and mailed pamphlets are still useful, but Chung emphasizes that “you’re going to have to be a little creative and broad in terms of how you go out and find people”- especially if you want to ensure your group accurately represents the racial diversity in our country.

Fittingly, the NIMH has its own Marketing and Community Relations Unit dedicated to helping recruit patients for studies conducted at the institute.

The UTD researchers have attended 30 to 40 events so far, says Ellen Morris, the lab manager and one of the therapists for the replication study. These include marathons, pizza parties and resource fairs. The researchers typically bring a large table to set up with candies, display, and flyers. They also present a model head to show how they monitor patient’s brain activity at different times throughout the study.

They also reached out to veteran-owned businesses such as coffee shops, tea shops and even cigar shops. There, they explain their research and request permission to put up flyers.

The lab members emphasize that the community in Dallas has been overwhelmingly positive about their ambition to study this new application of rTMS to treat PTSD. This could partly be explained by many people’s desire to contribute to the advancement of science by participating in a study like this.

Chung, of NIMH, says she has “found that a lot of people go into research for altruistic reasons. I see that every day in the clinical center. That is a noble thing that we want to respect and honor because we all benefit from that.”

The altruism arguably goes both ways. The UTD team helps clean late veterans’ headstones with the nonprofit Carry the Load along with other volunteering efforts. They also routinely provide resources for veterans who are suffering from PTSD or another mental illness but may not qualify for their study using rTMS.

Source: Read Full Article