Scientists at the University of Warwick have discovered a new process that sets the fastest molecular motor on its marathon-like runs through our neurons.

The findings, now published in Nature Communications, paves the way towards new treatments for certain neurological disorders.

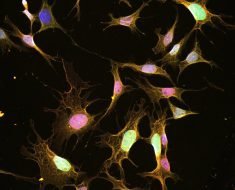

The research focuses on KIF1C: a tiny protein-based molecular motor that moves along microscopic tubular tracks (called microtubules) within neurons. The motor converts chemical energy into mechanical energy used to transport various cargoes along microtubule tracks, which is necessary for maintaining proper neurological function.

Neurons are cells that form the basis of our nervous system, conducting the vital function of transferring signals between the brain, the spinal cord and the rest of the body. They consist of a soma, dendrites, and an axon, a long projection from the cell that transports signals to other neurons.

Molecular motors need to be inactive and park until their cargo is loaded onto them. Neurons are an unusually long (up to 3 feet) type of nerve cell, and because of this marathon distance, these tiny molecular motors need to keep going until their cargo is delivered at the end.

Insufficient cargo transport is a crucial cause for some debilitating neurological disorders. Faulty KIF1C molecular motors cause hereditary spastic paraplegia, which affects an estimated 135,000 people worldwide. Other studies have also found links between defective molecular motors and neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

The research shows how, when not loaded with cargo, KIF1C prevents itself from attaching to microtubule tracks by folding on to itself. The scientists also identified two proteins: PTNPN21 and Hook3, which can attach to the KIF1C molecular motor. These proteins unfold KIF1C, activating it and allowing the motor to attach and run along the microtubule tracks—like firing the starting pistol for the marathon race.

The newly identified activators of KIF1C may stimulate cargo transport within the defective nerve cells of patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia, a possibility the team is currently exploring.

Commenting on the future impact of this research, Dr. Anne Straube from Warwick Medical School said: “If we understand how motors are shut off and on, we may be able to design cellular transport machines with altered properties. These could potentially be transferred into patients with defect cellular transport to compensate for the defects. Alternatively they can be used for nanotechnology to build new materials by exploiting their ability to concentrate enzymes or chemical reagents. We are also studying the properties of the motors with patient mutations to understand why they function less well.

Source: Read Full Article