They wash their hands until the skin hangs in tatters, are in a state of panic about bacteria and infections—and are unable to use common sense and distance themselves from the stressful thoughts that are controlling their lives.

Teenagers with the contamination and washing variant of OCD are not generally more ill than children and adolescents with other forms of disabling obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviour. However, if they have poor insight into their condition, they find it more difficult to recover and become healthy again as a result of the 14-week cognitive behavioural therapy, which is the standard form of treatment in Denmark for OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

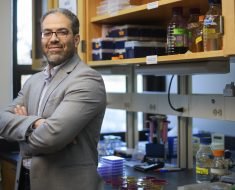

This is one of the conclusions of a newly published scientific study which Professor, Department Chair Per Hove Thomsen and Ph.D. student Sanne Jensen are behind. They are employed at Aarhus University and Aarhus University Hospital, Psychiatry, in Denmark.

“The research project shows that in the longer term, some of the patients who initially appear to react positively to cognitive behavioural therapy unfortunately turn out not to have received the help that they need. This is particularly true of young people with cleanliness rituals and reduced insight into their condition,” says Jensen.

“The tricky thing is that they initially react positively to the cognitive behavioural therapy, and they therefore leave the mental health services again after the 14-week period of treatment. But when we contact them again after three years, we can see they demonstrate a worrying development—they have gotten worse,” says Jensen about the research results, which have just been published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

Both she and the study’s senior researcher Per Hove emphasise that the research result does not in any way undermine the value of cognitive behavioural therapy, which is psychiatry’s modern active form of treatment. It is characterised by patients receiving help from a practitioner to practise doing more of whatever it is that they are afraid of, while simultaneously training a realistic relation to the outside world. Mental health service’s standard course of treatment lasts 14 weeks with a possible extension.

“Part of the overall picture is that almost eighty per cent of those we studied were so well-functioning following the cognitive behavioural therapy that after three years they no longer had OCD to a degree that required treatment,” says Per Hove Thomsen.

He refers to the findings that after the three-year period, researchers measured the same low level of symptoms as they did following the completion of the treatment in no less than 210 out of 269 of the children and adolescents between the ages of 7-17 who participated in the study. Only 59 or approx. one in five of the young people were in a worrying situation where there was fear of a relapse after the three years had elapsed.

“We’re fortunate that the study very precisely identifies the group which we should be keeping a close eye on after the end of the treatment, namely teenagers with cleanliness rituals/contamination anxiety and poor insights into their condition. This knowledge now needs to be disseminated to both clinicians and relatives,” says Per Hove Thomsen—well aware that the research results may lead to despondency among particularly vulnerable patients and their relatives. However, as he puts it:

“The conclusion isn’t that you’re doomed to a life-long disabling OCD if you’re a teenager with cleanliness rituals and poor insights into your condition. There are also young people from this patient group who don’t suffer a relapse. On the contrary, the conclusion is that we need to become better at following up on precisely these patients, because otherwise we risk leaving them in the lurch. Perhaps the treatment needs to be repeated, or perhaps there’s a need to supplement the treatment with SSRI medicine,” says Per Hove Thomsen.

Fact box: Many forms of OCD

Up to four per cent of all children and adolescents struggle with disabling obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviour to such an extent that they can be classified as suffering from OCD. Rituals and compulsive behaviour have many forms—for example:

Cleanliness rituals/contamination anxiety where the patient feels that they are gross or they are afraid of picking up a dangerous infection by touching something which someone else has already touched. Typical characteristics include avoidance behaviour (such as using an elbow to open doors) and attempts to remove the potential sources of the ‘contamination.’

Fear of causing harm by being somehow ‘wrong’ where the patient is afraid of doing harm to him- or herself or to others (by being a pyromaniac, murderer, sadist), or is afraid that they are e.g. a paedophile. Typical characteristics include anxiety that whatever it is the person fears is actually a disguised wish with the patient often uncertain as to whether his or her own impulses can be controlled.

Symmetry/hoarding where the patient must place objects or make movements in a specific order or form of symmetry, or has some other form of specific order such as repeating an action a specific number of times. The rituals often have to be performed in a specific way and are often so time-consuming that they are almost exhausting. Hoarding is characterised by a fear of throwing something away which should not have been discarded—ranging from letters to advertising and cast-off clothing.

The research results—more information

Source: Read Full Article