Stroke patients appear to receive better care at teaching hospitals with less of a chance of landing back in a hospital during the early stages of recovery, according to new research from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth).

The study, published today in JAMA Network Open, provides the first comprehensive nationwide analysis of 30-day readmission rates for both Medicare and privately insured patients with different types of stroke. It reveals that although readmissions have fallen by 3 percent a year on average between 2010 and 2014, patients discharged from nonteaching hospitals faced a significantly higher risk of readmission mainly due to having another stroke, related complications or septicemia, a serious blood infection.

“The research is important because readmissions have become a focus for improving quality of care while in a hospital, as well as reducing costs, and very little has been published about stroke patients at this scale,” said the study’s lead author Farhaan Vahidy, M.B.B.S, Ph.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of neurology at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. “Our findings help set national performance benchmarks for readmission levels among patients of all ages, types of stroke and insurance classes. This provides potential to identify specific groups for readmission reduction through targeted interventions that improve continued support for discharged patients, which should start before they leave the hospital doors.”

The overall decline in readmissions was not attributed to reduced stroke recurrence, which in fact increased in some cases, but more a result of a drop in readmission rates for other high volume conditions likely to affect stroke patients, who tend to be older and have additional health issues.

Results revealed more than 90 percent of all 30-day stroke-related readmissions were unplanned and, depending on the stroke type, up to 13.6 percent were deemed potentially preventable.

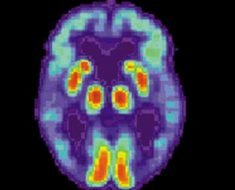

The greatest danger of readmission applied to patients with hemorrhagic stroke, a more serious form caused by a bleeding vessel in the brain, which carried a 13.7 percent likelihood. By contrast, patients with ischemic stroke, caused by a blocked vessel, faced a 12.4 percent risk.

“Many, but not all, patients with more severe stroke are transferred to an academic hospital, which were found to have a steady readmission rate regardless of how many stroke cases were admitted, suggesting superior care,” Vahidy said. “These patients are all inherently more vulnerable to stroke recurrence and associated conditions such as septicemia. Patients from nonacademic hospitals, however, seem to be even more prone to this happening as stroke patient volumes increase, indicating opportunities for improvement in pre-discharge patient care and transitional follow-up.”

Nonteaching hospital stroke patients accounted for around half (46.4%) of all patients and the disparity between readmission rates compared to teaching hospitals widened as the number of stroke patients treated at the nonteaching hospitals grew.

“The difference started to become statistically significant at hospitals discharging 300 stroke patients annually. For instance, at the 500 patient mark the increased risk of readmission is about 1 percent, which may not sound much, but it is because we’re talking about millions of patients,” Vahidy said.

Greater adherence to quality-of-care metrics, use of telestroke technology and organization of care delivery, as well as having adjoining outpatient clinics, were among the features common at teaching hospitals, which could give these centers a competitive edge in patient care, the researchers wrote.

The research therefore highlights a wealth of information which individual hospitals can use to identify issues and take measures to prevent secondary complications of stroke.

Source: Read Full Article