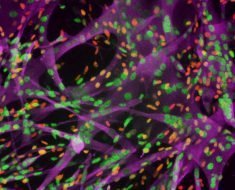

Scientists have developed a way to see brain cells talk – to actually see neurons communicate in bright, vivid color. The new lab technique is set to provide long-needed answers about the brain and neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia and depression. Those answers will facilitate new and vastly improved treatments for diseases that have largely resisted scientists’ efforts to understand them.

“Before, we didn’t have any way to understand how [such neurotransmissions] work,” said researcher J. Julius Zhu of the University of Virginia School of Medicine. “In the case of Alzheimer’s in particular, we spent billions of dollars and we have almost no effective treatment. … Now, for the first time, we can see what is happening.”

To demonstrate the technique’s effectiveness, Zhu’s team in Charlottesville and colleagues in China have used it to visualize a poorly understood neurotransmitter called acetylcholine.

“Acetylcholine has an important role in how we behave because it affects our memory and mood,” Zhu explained. “It affects Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, emotions, depression, all kinds of emotion-related diseases and mental problems.” (Acetylcholine also plays critical roles elsewhere in the body, such as regulating insulin secretion in the pancreas and controlling stress and blood pressure.)

Drugs designed to combat Alzheimer’s disease actually inhibit acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that degrades acetylcholine, to boost the effect of diminishing acetylcholine released in the brain, Zhu said. But doctors haven’t fully understood how the drugs work, and there’s been no way to determine just how much inhibition is needed.

“These drugs are not very effective,” he said. “They only offer a minor improvement, and once you stop the drug, [the symptoms] just seem much worse. So probably in trying to treat these patients, you temporarily enhance them but you actually make them even worse.”

By being able to see acetylcholine and other neurotransmitters in action in fluorescent color, doctors will be able to establish a baseline for good health and then work to restore that in patients.

“We want to first measure how [the neurotransmitters] normally do the job. We’ve already found that there are acetylcholine transmissions very different from what we would expect,” said Zhu, of UVA’s Department of Pharmacology. “Then we also want to find how the patient differs. That comparison will provide us important answers.”

Source: Read Full Article