My story begins eight years ago, when I was approached by my first client requesting that I supervise her in a therapeutic session with a psychedelic medicine.

She had debilitating depression and anxiety brought on by a breast cancer diagnosis. Although she had survived her cancer, she couldn’t shake her terrible emotional distress. She had tried therapists, pills and a residential program. Nothing had worked.

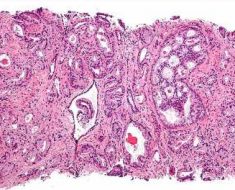

Then she came across stories in the media about research at UCLA using psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms) with cancer patients suffering from what was called “end-of-life distress” and how this new treatment was showing really promising results.

She was desperate to try it for herself.

Well, as a licensed therapist and academic, could I help this woman? Reading the research literature, I learned that psychedelic research was becoming well-developed as a treatment for the psycho-spiritual depression and “existential anxiety” that often accompany the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness.

I also found myself in a bind: The science was telling me that psilocybin is the treatment most likely to benefit patients with existential anxiety when other treatments have failed; my ethical code from the B.C. Association of Clinical Counsellors tells me to act to my client’s benefit; federal law forbids me to use this treatment.

This is why, together with colleagues in the Therapeutic Psilocybin for Canadians project, I filed an application with Health Canada in January 2017, seeking a so-called “Section 56 exemption” —to permit us to provide psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy to patients with terminal cancer.

Immediate decrease in death anxiety

Recent research at Johns Hopkins Medical Centre and New York University indicates that treatment of this end-of-life distress with psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy is safe and effective.

The research indicated it led to immediate, substantial and sustained decreases in depression, death anxiety, cancer-related demoralization and hopelessness.

It resulted in increased quality of life, life meaning and optimism. And these changes had persisted at a six-month follow-up.

Patients attributed improved attitudes about life and death, self, relationships and spirituality to the psilocybin experience, along with better well-being, life satisfaction and mood.

It is heartening to see research moving into Phase 3 clinical trials that will involve many more research participants. However, the foreseeable future for Canadians who need this game-changing therapy is not especially rosy.

At our current rate of progress, it may well still be years before psilocybin successfully completes Phase 3 trials and becomes available as an orthodox medicine.

Therapists risk criminal penalties

In the meantime, many Canadians with terminal cancer are also suffering from end-of-life distress, and are in dire need of relief —now.

They face serious and life-threatening illness. Their condition is terminal, so concerns about long-term effects of psilocybin are not relevant. They suffer from serious end-of-life psychological distress (anxiety and depression) to the point that it interferes with their other medical treatments. And this distress has not successfully responded to other treatments.

Psilocybin is currently a restricted drug, meaning that therapists risk criminal penalties if they aid or abet its possession. That means that we cannot recommend or encourage its use.

My professional Code of Ethics, however, states that our ethical duty is to act in a way that serves our clients’ “best interests.” The service we provide has to be “for the client’s benefit.” We must “take care to maximize benefits and minimize potential harm.”

A compassionate, humanitarian death

I agree with the Canadian medical establishment that, in ordinary circumstances, new medicines should be made available to Canadians only when they have successfully completed Phase 3 clinical trials.

But I contend that the patients described here are not in ordinary circumstances. They have terminal cancer. All other treatments have failed them; they have nothing left to lose. They have the right to die; surely they have the right to try!

These patients deserve access to a still-experimental but promising medicine on compassionate and humanitarian grounds. Because of their extraordinary medical straits, psilocybin now for them represents a reasonable medical choice; it is necessary to them for a medical purpose.

Our application to Health Canada seeking a “Section 56 exemption” will be ruled on very shortly.

We fully expect that it will be denied —for political, not scientific reasons. Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government is likely in no mood to loosen up on psychedelics before the dust from the legalization of cannabis has fully settled. I think the government would like it if someone else made that decision.

Violation of our rights and freedoms

If our application is denied, we intend to file for a judicial review, and if necessary, a lawsuit in Federal Court challenging that denial.

We believe that prohibition of access to psilocybin for a legitimate medical purpose violates a citizen’s Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Section 7 right to “life, liberty and security of person.”

This clause has already been interpreted by the Supreme Court to imply that a citizen has the right to autonomy in making health-care decisions. Charter-based arguments have already led to success in three recent landmark medical cannabis cases.

We argue that what applies to cannabis also applies to psilocybin: “The prohibition of … cannabis ‘limits the liberty of medical users by foreclosing reasonable medical choices through the threat of criminal prosecution. Similarly, by forcing a person to choose between a legal but inadequate treatment and an illegal but more effective one, the law also infringes on security of person.'” Supreme Court of Canada, R. v. Smith, 2015

Source: Read Full Article