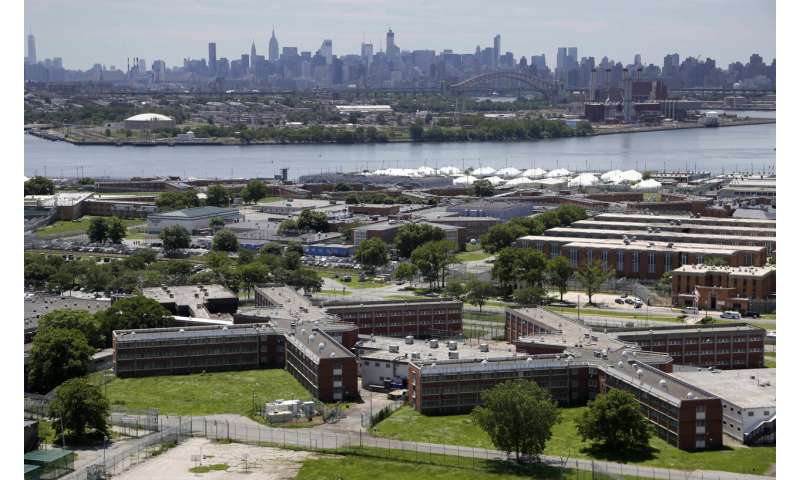

The board overseeing New York City’s jails urged officials to start releasing vulnerable populations and those being held on low-level offenses as the coronavirus outbreak hit the notorious Rikers Island complex and nearby jails—infecting at least 38 people.

Another inmate, meanwhile, became the first in the country to test positive in a federal jail.

“Fewer people in the jails will save lives and minimize transmission among people in custody as well as staff,” Board of Correction interim chairwoman Jacqueline Sherman wrote in a letter to New York’s criminal justice leaders this weekend. “Failure to drastically reduce the jail population threatens to overwhelm the City jails’ healthcare system as well its basic operations.”

Sherman pushed for the release of more than 2,000 people in custody in New York City jails, including those over 50 years old; those with health conditions such as lung and heart disease; those being held for parole violations, such as missing a curfew; and those serving sentences of less than a year.

Such steps are needed, she said, to stem the tide of COVID-19.

Mayor Bill de Blasio said 23 inmates were set to be released Sunday, all older and at a low risk of offending again, and 200 additional inmates were being reviewed for release.

More than 2.2 million people are incarcerated in the United States—more than anywhere in the world—and there are growing fears that an outbreak could spread rapidly through a vast network of federal and state prisons, county jails and detention centers.

It’s a tightly packed, fluid population that is already grappling with high rates of health problems and, when it comes to the elderly and the infirm, elevated risks of serious complications. With limited capacity nationally to test for COVID-19, men and women inside worry that they are last in line when showing flu-like symptoms, meaning that some may be infected without knowing it.

The first positive tests from inside prisons and jails started tricking out just over a week ago, with less than two dozen officers and staff infected in facilities spanning from California and Michigan to Pennsylvania. New cases pop up almost every day.

From the start, public officials and advocates called for a reduction in the size of their jail and prison populations, saying they were a tinderbox for the virus, not just inside correctional facilities, but society at large. Hundreds of incarcerated men and women have already been released, including 600 in Los Angeles and 300 in San Francisco. Other places talking about early releases include Travis County, Texas, and Cuyahoga County, Ohio.

“It’s like an approaching tsunami. Once it hits, it’s too late,” said James Pingeon, an attorney with Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts. “I get that opening the doors of all the prisons is not realistic, but we should release as many that it’s safe to release in order to avoid a situation like the one at Rikers.”

The coronavirus outbreak in New York City jails was the largest so far nationwide.

More than half of the 38 who tested positive were people who were incarcerated.

New York State Senator Luis Sepúlveda and Assemblyman David Wepin wrote to Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Thursday, asking him to convene an emergency committee to review all state prison inmates for possible early release. In addition to those at high risk of infection and non-violent offenders within three years of their release date, they said individuals convicted of violent crimes with just one year left should also be considered.

In Chicago, prominent civil rights groups led by the Uptown People’s Law Center last week made a similar call to Gov. J.B. Pritzker, adding prisoners scheduled to be paroled within 120 days and those who are pregnant or living with infants should also be among those considered for early release.

The Law Center argued that simple measures to prevent the spread of the new Coronavirus are impossible to carry out in a prison setting, noting that hand sanitizer is viewed as contraband due to its alcohol content, and covering one’s mouth while coughing is impossible while handcuffed.

Alan Mills, the Center’s executive director, said state officials claim they are distributing more soap and allowing hand sanitizer inside, while men at Stateville Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison in Crest Hill, Illinois, tell a different story.

“My sources at Stateville tell me that none of that has been distributed to inmates,” he said. “It’s been distributed to staff.”

A man incarcerated in New York City, meanwhile, became the first confirmed case in the federal prison system on Saturday.

The man, who is housed at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, complained of chest pains on Thursday, a few days after he arrived at the facility, the federal Bureau of Prisons told the AP. He was taken to a local hospital and was tested for COVID-19, officials said.

He was discharged from the hospital on Friday and returned to the jail, where he was immediately placed in isolation, the agency said, adding medical and psychiatric staff were visiting him routinely.

Others housed with the man are also being quarantined, along with staff members who may have had contact with him.

Anthony Sanon, head of the American Federal of Government Employees local representing correction officers at the Metropolitan Detention Center, called on the Bureau of Prisons to immediately stop transferring people from one institution to another.

“There should not be any type of movement from institution to institution,” Sanon said. “We need to stop all movement in the Bureau Prisons.”

There have been two positive cases among BOP staff members: an employee who works at an administrative office in Grand Prairie, Texas, and another employee who works in Leavenworth, Kansas, but who officials said did not have contact with inmates since becoming symptomatic.

Source: Read Full Article