MONDAY, Nov. 9, 2020 — American presidential elections are clearly divisive, but a new analysis suggests they may trigger depression in residents of states that favored the losing candidate.

The investigators gauged the mental health of roughly half a million Americans after the 2016 presidential election. The upshot: Stress and depression risk went up significantly in those states that had gone for Hillary Clinton.

“We found that the number of poor mental health days that adults in Clinton states experienced rose 15% from October to December 2016,” said study author Brandon Yan. “That’s half a day more per adult — and 55 million more days of stress, depressed mood, and emotional distress in total — for adults living in Clinton-voting states in December alone.”

And that rise continued through the first half of 2017, added Yan, who is a medical student and health policy researcher with the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and School of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

None of those findings are surprising, said clinical psychologist Lynn Bufka. Though not involved in the study, she’s a member of the American Psychological Association’s “Stress in America” team.

“People had a lot of emotional investment in the 2016 election, and the current outcome as well,” Bufka noted. “They really want certain outcomes, and if they don’t get what they want it can be very, very disappointing.”

That disappointment is not without foundation, she added. “There may be truth in anticipating that a certain outcome could mean x, y or z, in terms of having a real and perhaps negative impact on a voter’s life,” Bufka noted. “Final decisions really do mean certain things. And for certain voters, it may be reasonable that they would be concerned about those things.”

To explore the topic, Yan and his colleagues pored over survey data collected across all 50 states between May 2016 and May 2017.

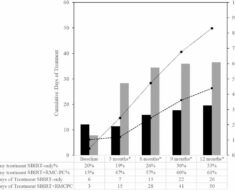

Among the 20 states that went for Clinton, residents indicated that the number of days during which they experienced stress, depression or emotional problems rose from nearly 3.4 days in October 2016 to nearly 3.9 days in December 2016. The team also found a 2-percentage-point rise in the number of Clinton state residents who said they experienced “poor mental health” — an indicator of clinical depression — for two weeks or more a month post-election.

In Trump-voting states the opposite unfolded: Poor mental health risk dipped from an average of just over 3.9 days per month in October 2016 to just under 3.8 days in November 2016.

Yan pointed out that living in an election-losing state doesn’t mean you’re at very high risk for post-election stress, only that your risk may rise.

But the degree of that risk may go up, depending the margin of loss. For example, in states with a 10-percentage-point greater margin of Clinton support there were 0.41 more days of worse mental health per adult in December 2016. In Trump states, the reverse was true: A 10-percentage-pont higher margin of support predicted 0.41 fewer days in worse mental health risk.

The bottom line: “Elections matter, including for health,” Yan said.

“Elections may not seem like events that would themselves impact public health,” Yan noted, “but this study shows us that we should pay attention to their health effects.”

In the face of a fresh Joe Biden victory, what can Trump voters do to lessen their post-election risk?

“Remembering that you’re not alone in feeling stress and anxiety, and that there are people, health care providers included, who could offer support and resources,” Yan suggested.

“And focus on what you can control,” Bufka added. “Turn off the TV. Set boundaries. Be selective in where you get your news and information. Social media may not be the best place for it. And it’s really important to pay attention to your well-being. Of course, you can’t suddenly do that on Election Day. You need to pay attention to it all the time in order to develop healthy habits, so you get the sleep you need and are able to moderate stress.

“I also think it’s going to be critical to stop demonizing people who think differently than us,” she added. “Everyone wants a job, to enjoy time with friends and family. We might have different ideas as to how to get there. But we can and should focus on that goals we perhaps share in common and all want to achieve.”

The study findings were published recently in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Source: Read Full Article