New vaccine could prevent up to 80% of staph infections that kill more than 30,000 hospital patients in the US a year, animal study suggests

- Researchers infected mice and rabbits with S. aureus, a common type of bacteria found on the skin that can lead to skin, bone and blood infections

- Beforehand they received a vaccine that targets biofilm, a bacterial substance that is resistant to the immune system’s antibodies and antibiotics

- 80% of infected mice who were vaccinated survived and two-thirds cleared the infection in three weeks compared to 10% of the unvaccinated mice

- Two-thirds of the immunized rabbits cleared their S. aureus infections in one month compared to none of the controls

A new experimental vaccine may be able to protect against staph infections that kill tens of thousands of US hospital patients every year.

In research conducted in mice and rabbits, scientists tested their vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus, a common bacteria found on the skin and the leading cause of skin and soft tissue infections.

More than 80 percent of the vaccinated mice survived and they were six times more likely to clear the infection than the unvaccinated rodents were.

And among rabbits, two-thirds of the immunized group had cleared the infection in comparison with none of the group that didn’t receive the jab

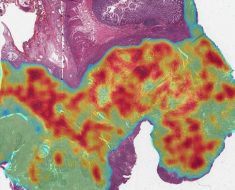

The vaccine, developed by the University of Maryland in Baltimore, targets biofilm, a substance in chronic S. aureus that is resistant to antibodies released by the immune system or antibiotics.

Researchers from the University of Maryland in Baltimore have developed a vaccine that may protect patients from the deadly effects of an infection call by S. aureus bacteria (file image)

S. aureus is a common type of bacteria found on the skin, in nasal cavities and in the respiratory tract.

It is frequently the cause of food poisoning, skin infections such as abscesses, and respiratory infections including sinusitis.

While most staph infections are not serious, S. aureus can cause bloodstream infections, pneumonia, or bone and joint infections.

It is among the most common of hospital-acquired infections, causing more than 30,000 deaths in the US every year, and costing the healthcare system around $10 billion.

Scientists have been attempting to develop a vaccine for S. aureus for years, but none have been approved.

To develop this new vaccine, the team screened S. aureus proteins that antibodies attempt to kill during a chronic infection.

‘This method permitted us to select protein targets for vaccination that were both expressed during an infection and were capable of being recognized by the immune response,’ said corresponding author Dr Janette Harro, a research assistant professor at the University of Maryland in Baltimore.

The team’s jab attacks five different proteins, four of them being bacterial biofilm, a slimy substance that protects bacteria from immune responses such as antibodies or antibiotics.

For the study, published in the journal Infection and Immunity, researchers injected mice and rabbits with the vaccine, and then infected them with the bacteria.

Controls were only injected with the bacteria, not the vaccine.

Among the rabbits, two-thirds of the vaccinated rabbits had cleared the infection 24 days after being infected, but none of the unvaccinated rabbits had.

Researchers had injected the bacteria into the bone marrow, and control rabbits had hole-like lesions within the bone.

But the immunized rabbits had fewer lesions or none at all.

Meanwhile, in mice – who are more likely to die of S. aureus – 80 percent of those who were vaccinated survived and two third were able to clear the infection compared to 10 percent of the controls.

Twenty-one days after the infection, the mice that survived had regained any weight lost and didn’t show any signs that they’d been ill, like ruffled fur.

The team says it know the findings may not directly translate to humans, but hopes to test their vaccine soon.

An effective vaccine against S. aureus ‘would have enormous therapeutic utility in patients undergoing surgery, especially orthopedic and cardiovascular procedures where medical structures or devices are implanted,’ said Dr Harro.

Source: Read Full Article