A catheter based procedure to close a type of ‘hole in the heart’ followed by antiplatelet drugs (e.g. aspirin) should be recommended for patients under 60 years old, who have also had a stroke, say a panel of experts in The BMJ today.

The procedure involves slowly moving a catheter (a long, thin, flexible tube) into the heart to close the hole. Most guidelines currently advise against the closure procedure and instead recommend taking life long anti-clotting drugs to prevent further strokes.

The panel’s recommendation is based on new evidence that closure reduces the risk of future stroke more than drug treatment alone, even though catheter based closure itself carries a risk of complications.

For patients who need or want to avoid the procedure, the panel makes a weak recommendation for anticoagulation over antiplatelet therapy, based on the fact that patients value preventing strokes more than they are concerned about risk of bleeding.

Their advice is part of The BMJ‘s ‘Rapid Recommendations’ initiative—to produce rapid and trustworthy guidelines based on new evidence to help doctors make better decisions with their patients.

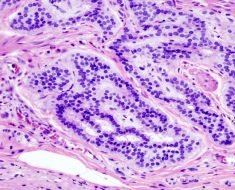

The recommendation only applies to patients that have a particular type of ‘hole in the heart’ called patent foramen ovale (PFO) – a hole in the wall that divides the top two chambers of the heart which has not closed naturally after birth.

Up to one in four people have a PFO and for most, it does not cause any problems. This guideline only recommends having the hole closed if the person has had a stroke, and there is no other obvious cause (known as “cryptogenic” stroke).

PFO closure, antiplatelets and anticoagulants are designed to reduce the risk of a second stroke.

The downside of the procedure is that 3.6% of patients will experience an adverse event, but these are usually associated with only short term effects, so may not be as important to patients as cutting their risk of stroke, they suggest.

Three large clinical trials published in 2017 suggested PFO closure might reduce the risk of stroke more than drug treatment alone.

So an international panel made up of doctors, heart and stroke specialists, and people with experience of PFO and cryptogenic stroke, reviewed the latest evidence to see if it might be strong enough to change clinical practice.

Using the GRADE approach (a system used to assess the quality of evidence). They compared three options; PFO closure and antiplatelets to antiplatelets alone; PFO closure compared to anticoagulants; anticoagulants compared to antiplatelets.

However, the panel stresses that doctors should discuss options with the patient, ideally as part of a shared decision making process.

Because PFO closure is associated with higher costs, implementation of this recommendation is likely to have an important cost impact for health funders in the short term, adds the panel. Over the long term, however, they say PFO closure “may reduce costs as a result of reduced stroke rates and reduction in associated costs.”

They conclude that further trials are needed to address remaining uncertainties, and that new evidence must be assessed to judge to what extent it may alter the recommendation.

Panel member Bray Patrick-Lake, founding director of the not-for-profit PFO Research Foundation, says: “PFO patients suffering cryptogenic stroke have experienced confusion when navigating the treatment decision making process and reported receiving recommendations based on physician’s preference rather than an unbiased assessment of available clinical trial data.”

She adds: “The BMJ working group included patient representatives in the critical assessment of PFO research and thoughtfully produced evidence that can help patients understand what their outcomes are likely to be with available therapies so they can work with their physicians to make an informed treatment decision which incorporates their values and preferences.”

Source: Read Full Article