One of the outstanding questions in neurodevelopment research has been identifying how connections in the brain change to improve neural function during childhood and adolescence. Now, results from a study in rats just reported by neuroscientists Heather Richardson, Geng-Lin Li and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Amherst suggest that as animals transition into adolescence, specific physical changes to axons speed up neural transmission, which may lead to higher cognitive abilities.

Their co-author, doctoral candidate Andrea Silva-Gotay, says, “One advantage of increased conduction speed is faster processing of information; brain areas communicate faster and decisions can be made faster.” Two factors that can increase conduction speed are myelination and larger axon diameter, she adds. “A thin axon will be slower, a thick one faster. Myelin can also make axons faster.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study that combines measurement of conduction velocity of axons with measurements of myelination during development in this part of the brain,” Silva-Gotay points out.

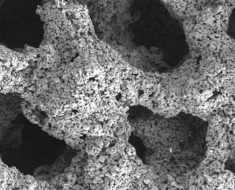

Writing in the journal eNeuro, the researchers report that they have identified specific developmental changes that may be key factors underlying enhanced neural processing in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of the maturing rat brain. This is a region that integrates information from many sources to process and modulate complex functions such as stress responses, behavior control, attention, and working memory, Richardson says.

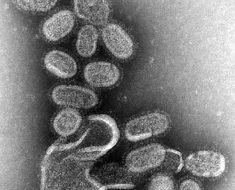

She and colleagues studied changes in axons—the long conducting threads of a nerve cell along which signals move from one cell to another—and the wrapping of these axons by myelin—the electrically insulating sheath that forms around nerve fibers at this time—in brains from groups of juvenile, pre-adolescent rats at 15 days old and mid-adolescent rats at 43 days old.

Results suggest that in animals two-to-six weeks old, axons in the mPFC undergo microstructural and electrophysiological changes that speed up neural transmission. Silva-Gotay explains, “Between those two ages we found a significant increase in how fast the electrical signals travel in the brain during pre-adolescence compared to adolescence. There is a dramatic increase. Moreover, we found this in the mPFC, which was not known before.”

The authors report that signal conduction velocity in axons nearly doubled by mid-adolescence, and this corresponded with a 90-fold increase in the number of axons that were myelinated in this region. “Because axonal diameter did not change with age, we reason that myelination of these axons accounts for the significant increase in speed,” senior author Richardson says. “These axonal changes could contribute to some of the developmental improvements in how well the prefrontal cortex works.”

Source: Read Full Article