Food is, generally speaking, a good thing. In addition to being quite tasty, it is also necessary for survival. That’s why animals have evolved robust physiological systems that attract them to food and keep them coming back for more.

Now, research in mice reveals the existence of brain cells that have the opposite effect, curbing an animal’s impulse to eat. Published in Neuron, the study shows that these cells also play a role in regulating memory, and are part of a larger brain circuit that promotes balanced eating.

The belly and the brain

Historically, researchers have thought of feeding as a visceral, instinctive process: An animal smells or sees an appealing snack and, without hesitation, proceeds to eat said snack. However, an increasingly detailed picture is now emerging in which mental processes inform animals’ decision to either consume or refuse a meal.

A human, for example, may consider, “I’m supposed to be at brunch in 20 minutes, so I better save my appetite.” Though other mammals may not have the equivalent internal monologue, there is reason to suspect that their eating habits do involve complex cognition. For example, research has shown that defects in the hippocampus—a brain area involved in memory—can alter feeding behavior, suggesting that past experiences influence an animal’s attraction to food.

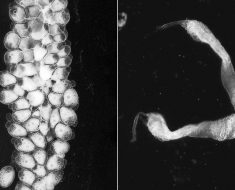

Building on this research, Estefania Azevedo, a postdoctoral associate in the lab of Jeffrey M. Friedman, recently identified a group of hippocampal cells, known as hD2R neurons, that become active whenever a mouse is fed. Collaborating with Paul Greengard, the Vincent Astor Professor, and Jia Cheng, a postdoctoral associate in his lab, the researchers also found that when these neurons were stimulated, mice ate less; and when they were silenced, they ate more. In short, hD2R neurons respond to the presence of food by deterring animals from eating that food.

Interpreting these findings, Azevedo says that, though animals usually benefit from eating the snacks in front of them, in some instances it is useful to exercise restraint. For example, if an animal has recently eaten, then searching for another meal is both unnecessary and risky, as foraging exposes animals to predators. The newly discovered neurons, it seems, help animals stop feeding when it no longer behooves them.

“These cells keep an animal from overeating,” says Azevedo. “They appear to make eating less rewarding and, in that sense, are tuning the animal’s relationship to food.”

Everything in moderation

In the wild, you can’t eat unless you know where to find food. Fortunately, brains are quite good at remembering the location of past meals: When an animal encounters sustenance in a particular locale, it makes a mental connection between the place and the food. To test how hD2R cells might affect these connections, Friedman and Azevedo stimulated the neurons as mice wandered around a food-filled environment. This intervention, they found, made mice less likely to return to the area in which food was previously located—suggesting that hDR2 activation somehow diminishes meal-related memories.

“Mental connections between food and location are important for survival, and the strength of these connections is regulated by how rewarding an experience is,” says Azevedo. “Because hD2R neurons affect an animal’s relationship with food, it also ends up affecting these connections.”

Further experiments showed that hD2R neurons receive input from the entorhinal cortex, which processes sensory information, and send output to the septum, which is involved in feeding. The first to identify this brain circuit, the researchers conclude that the neurons serve as a regulatory checkpoint between sensing food and eating food.

Together with analyses of other neural circuits, this research suggests that the brain has elaborate mechanisms for fine-tuning appetite: While some systems help an animal remember and find food, others restrain food intake.

Source: Read Full Article