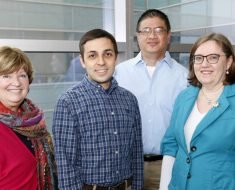

An international group of researchers led by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Assistant Professor Gholson Lyon has identified a new genetic mutation associated with intellectual disability, developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, abnormal facial features, and congenital cardiac anomalies.

The genetic mutation, which can run in families, is related to the mutation underlying Ogden syndrome, a much more serious condition that shares many of the same symptoms.

In 2011, Lyon and his colleagues published the first paper about Ogden syndrome, named for the Utah town in which five boys across two generations of a single family were struck down by the disease before age 3. Caused by a mutation in a gene called NAA10, Ogden is an X-chromosome-linked condition, meaning only males are afflicted.

In the years since Ogden’s discovery, Lyon has been collecting information on individuals with mutations in a related gene called NAA15. It bears the blueprint for a protein that works alongside the NAA10 protein in a cellular mechanism that modifies other proteins. This mechanism is called NatA-mediated N-terminal acetylation.

Lyon was made aware of the first individual with what he calls “NAA15-related disorder” by clinical geneticist Wendy Chung at Columbia University. She and colleagues had published a paper in which they described a boy with a mutation in NAA15 who had congenital heart defects as well as developmental delays and intellectual disability. Lyon and colleagues have since collected referrals from clinicians around the world that have identified a total of 37 individuals in 32 families with a mutation in NAA15. They include both men and women, as the NAA15 gene is not located on the X chromosome. Dr. Holly Stressman of Creighton University and Dr. Linyan Meng of Baylor College of Medicine were co-senior leaders of the team, with Dr. Lyon.

“Trying to prove the relevance of any mutation in a gene requires a large number of samples,” Lyon says. “As a result, we’re seeing the field of human genetics move more toward this type of large-scale collaboration.” This points to the future promise of this research, he suggests. “As the price of genetic sequencing drops and more people are sequenced, we may be able to provide individuals with such mutations with more education and services in early life which could lead to better overall functioning.”

Source: Read Full Article