Two new studies provide evidence that previous Dengue infection in pregnant mothers may lead to increased severity of Zika in babies, and that previous Zika infection in mice mothers may increase severity of Dengue infection in their pups. The research, publishing November 14 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, supports that maternally-acquired antibodies for one virus can assist infection by the other by a process unique to flaviviruses.

“We’ve seen Zika infections in humans decrease from their peak in 2016, but it is still a significant concern and might re-emerge,” says senior author Mehul Suthar (@SutharLab)?, a viral immunologist at Emory University whose team studied human placental tissue to find out how Dengue antibodies help transport the Zika virus across the placental barrier. “The regions where Dengue and Zika are prevalent overlap extensively, so it’s important to understand how immune responses to one may influence vulnerability to the other.”

“There’s a prevailing attitude that antibodies are always good, but antibodies can have a range of effects,” says Sujan Shresta, an immunologist at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology whose group showed that mice born to Zika-immune mothers were more vulnerable to a deadly form of Dengue fever. “We need to embrace this complexity to develop the most effective vaccines.”

Dengue and Zika are both flaviviruses, which use RNA as their genetic material and usually spread to humans by hitching rides on mosquitos. Both diseases concentrate in tropical and subtropical areas where the Aedes mosquito thrives. While at first Dengue causes a relatively mild fever, subsequent infections raise the risk of developing a deadly hemorrhagic form. Only one Dengue vaccine exists for use in limited cases. Zika infection during pregnancy causes mild to moderate fever symptoms in the mother and can cause brain defects such as microcephaly in the fetus. No approved Zika vaccines exist as of today.

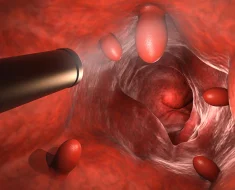

Suthar and his team, including co-first author and MD/PhD student Matthew Zimmerman at Emory University, examined how Dengue antibodies affect the ability of Zika to infect the placenta. When they introduced Dengue antibodies and the Zika virus to donated placental tissue, the Dengue antibodies bound to Zika due to similarities in the proteins that envelope the virus. However, the Dengue antibodies failed to neutralize the Zika virus, instead transporting the still-pathogenic form into cells of the placenta.

“These antibody-antigen complexes will bind to Fc receptors on placental macrophages, the normal function of which is to take up immune complexes and destroy the antigens bound to them,” says Zimmerman. “This cross-reactivity between the viruses and their antibodies allows more of the virus to enter these placental macrophages much more readily.”

“Our studies reveal that flaviviruses have a potentially unique way of crossing the placental barrier,” says Suthar. “This antibody-dependent enhancement poses a challenge for disease prevention.”

In Shresta’s study, her team showed that Zika antibodies can also enhance Dengue. They found that mouse pups born to mothers with circulating Zika antibodies were less likely to contract Zika, but more likely to die from Dengue, than those with Zika-naïve mothers. When she and her team studied the mice’s blood, they saw that the mothers had passed their Zika antibodies down to their pups. Mirroring Suthar’s observations, the maternally-inherited Zika antibodies bound to the Dengue virus but did not inactivate it.

“Here, the immune response acts as a double-edged sword, protecting against one infection while enhancing another,” says Shresta. “That means we should be careful when designing vaccines, or we may prevent one disease while unintentionally increasing vulnerability to the other.”

More studies are needed to uncover whether other flaviviruses, such as West Nile and yellow fever, also increase the offspring’s vulnerability to each other. As mosquitos carrying these viruses spread farther and the threat of infection rises, Shresta believes there is a need to develop pan-flaviviral vaccines that would be effective against both Dengue and Zika.

“More and more evidence shows that antibody-dependent enhancement could be a global health concern,” says Shresta. “This is just one process in a range of complicated immune responses that we should consider as we develop more effective, longer-lasting vaccines.”

“Our findings highlight the fact that we still know little about disease transmission from mother to baby,” adds Suthar. “We now have a model system to better understand Zika infection of the placenta. We want to use that to understand more about Zika’s persistence in the placenta and to discover whether other flaviviruses follow a similar route from mother to baby.”

Source: Read Full Article