Memorial Day is traditionally a day for remembering American service members who died in armed conflict, but it’s also important to remember those who died by suicide after returning home with severe emotional and physical scars.

About 20 veterans die by suicide each day, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs, which noted in its latest report on veteran suicides that rates have been climbing for both veterans and non-veterans.

This issue is not new and there are already several bills passing through the House with the goal of helping veterans.

“One of the tragedies is that many of those veterans who take their lives come from my father’s era, Vietnam,” Secretary of Veteran Affairs Robert Wilkie told The Associated Press last month. “So we have Americans whose problems in some cases began building when Lyndon Johnson was president. We have to tackle this issue in a way that we haven’t tackled it before.”

Suicide is the 10th-leading cause of death for all Americans, and the national rate has increased in nearly every state since 1999, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide affects people of all backgrounds, ages and professions.

Dealing with suicide in the military community is similar to the general public, but there are some cultural differences that make it uniquely challenging, according to Kim Ruocco, vice president of suicide prevention and postvention at the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors, a nonprofit that provides peer support to grieving military families, including those bereaved by suicide loss.

“Suicide is a complex event with multiple factors that contribute to it,” Ruocco said. “Mental health may be one of the factors, but in the military, there are other contributing factors, such as moral injuries, survivor guilt, unresolved grief and exposure to trauma [and] loss of identity and community, which contributes to the struggles of those who serve.”

Ruocco said that pride may also get in the way of seeking help.

“Veterans often compare their own struggles to those around them. In their mind, they often don’t deserve care because someone else is suffering more or has a visible injury,” she said. “There’s a culture of ‘suck it up, push through, don’t get help.’ It’s very focused on the mission, focused on taking care of others and not being the weakest link.”

Ruocco is not only a licensed social worker, she’s also a military widow. Marine Major John Ruocco, a decorated Marine Cobra helicopter pilot who flew 75 combat missions, took his own life while preparing for a second combat deployment to Iraq in 2005.

The mother of three said that every death by suicide directly impacts 135 people. She also knows that the chances of suicide in a family are amplified once someone dies by suicide. Those are the people Kim is trying to help at TAPS.

She uses a technique called postvention, which is meant to support the family, friends and peers of the person lost to suicide. It’s also how she honors her husband.

“How do I continue his story in a way that is not just focused on how he died, but to bring hope and healing and understanding along with that?” she said. “I think he’d be really proud that I took a terrible event and made some meaning out of it by giving hope to others.”

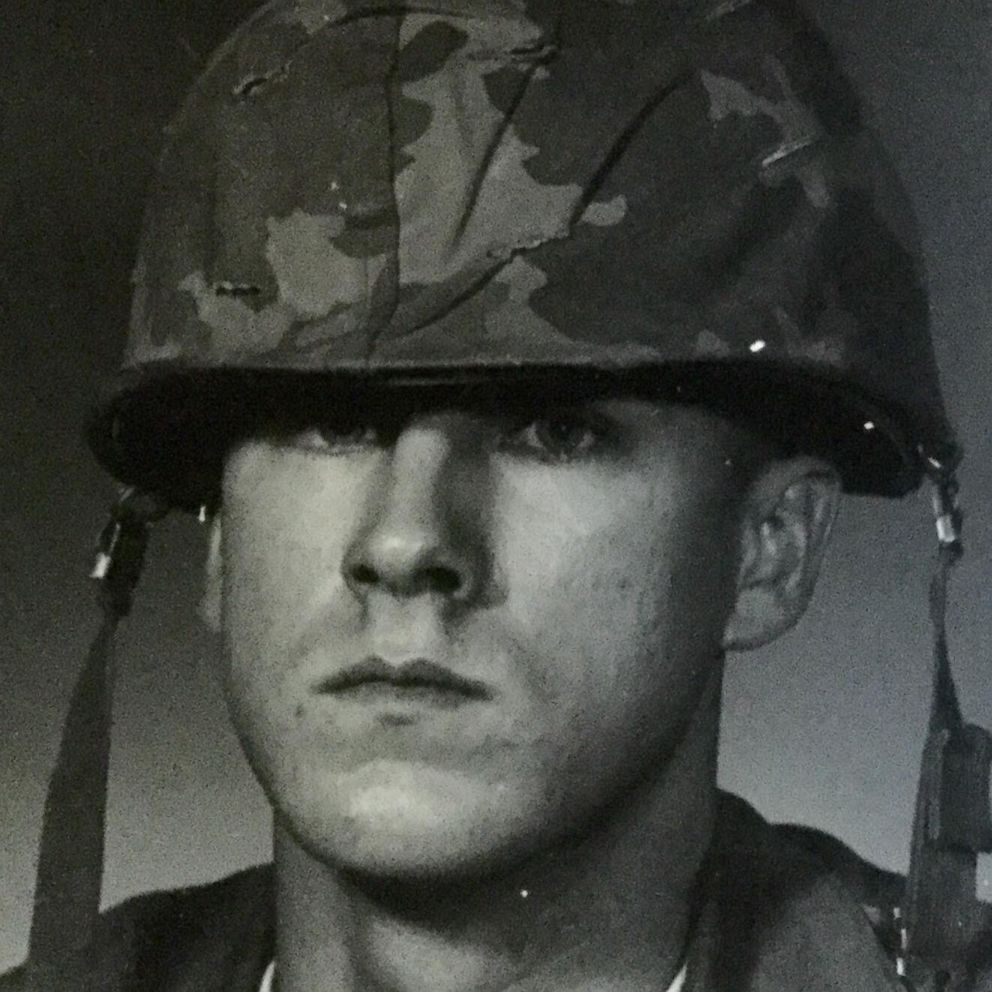

Her work has helped people like Dana O’Brien, a Vietnam War veteran from South Carolina. He recently told ABC News Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Jennifer Ashton about coming back from Vietnam a very withdrawn person who chose to numb his pain rather than talk openly about it.

“The unit I was with, there’s 747 names on the Vietnam Wall in a 10-year span. The 1/9 were the ‘walking dead.’ They lost more men and were in [the] country longer than any other unit in Marine Corp. history,” O’Brien said.

When O’Brien greeted Ashton, he told her that his friends call him “O.B.” and then offered a smile and embrace after mentioning that his Marine grandson, Daniel, died by suicide.

“I’m a hugger,” he said, adding that his work with other families has been a gift in disguise, as they’ve turned him into an outgoing, burly bear-hugger.

“Before Daniel took his life, I wasn’t like that. Before I went to TAPS, I wasn’t like that. Before I became a peer mentor, I wasn’t like that,” he said. “After I became a peer mentor, it was like a big tooth on a key that had unlocked that closet that had been yearning to be unlocked for over 40-plus years. I think it was a gift from Daniel.”

TAPS uses three phases to help survivors. First is stabilization; then grief work, helping those who are grieving to move away from focusing on how a person died to focus on how they lived; and, finally, post-traumatic growth, or finding meaning in the loss, such as using it as motivation to prevent other suicides.

“We don’t get over grief — it’s a lifelong journey”, Ruocco said she tells families. [It’s about] “teaching families how to grieve and then helping them move away from the cause of death to how the person lived and served. Then, once they’ve gone through that process, they can find growth — meaning in their life in honor of their loved one.”

Ruocco guessed that “O.B.” has saved hundreds of lives by traveling around the country and talking to other loss survivors.

“He’s the greeter at our seminars. People come in broken like he was. He knows, he can see that,” she said. “He’s calling and checking on people. All these people that are at risk and have all this horrific loss are at a very unstable time in their lives and he’s giving them that hope and that roadmap to getting through it.”

“O.B.” tells people not to wait to get help as he did, and reminds them that there are many resources that can help.

“He’s an example of exactly what we need in the military — an ability to be more vulnerable about what you’re feeling and the impact of what you’ve been through in your life,” Ruocco said. “Then, using that to be a better [service member], to be a better person. He’s taken a risk to be vulnerable and then to use what he’s been through to help others, and that’s really where we need to be when we’re talking about mental health and wellness and fight against suicide.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, contact the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) where you’ll be put in touch with a local crisis center. There are also specific resources available for military families. For more information about TAPS programs, visit its website call 800-959-TAPS, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Eric M. Strauss is the managing editor of the ABC News Medical Unit and he welcomes your feedback on Twitter. Please subscribe to ABC News’ free podcast, “Life After Suicide,” which covers strategies for dealing with a sudden loss.

Source: Read Full Article