French investigators are warning clinicians who treat patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) not to initiate treatment with sotorasib within 30 days of an immunotherapy infusion with an anti-programmed cell death–ligand-1 (anti-PD-L1) inhibitor because of the risk of increased toxicity.

Sotorasib is indicated for adults with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC who carry a KRASG12C mutation, which occurs in about 13% of cases.

Since its approval in 2021, sotorasib has emerged as “a new standard of care” for such patients after chemotherapy and anti-PD-L1 failure, the investigators say.

The new warning comes after the team compared 48 patients who received an anti-PD-L1 ― most often pembrolizumab alone or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy ― before sotorasib with a control group of 54 patients who either didn’t receive an anti-PD-L1 before sotorasib or had at least one other treatment in between.

The team found that sequential anti-PD-L1 and sotorasib therapy significantly increased the risk of severe sotorasib-related hepatotoxicity and also the risk of non-liver adverse events (AEs), typically in patients who received sotorasib within 30 days of an anti-PD-L1.

“We suggest avoiding starting sotorasib within 30 days from the last anti-PD-(L)1 infusion,” say senior author Michaël Duruisseaux, MD, PhD

Louis Pradel Hospital, Bron, France, and collegues.

The findings should also “prompt a close monitoring for the development of hepatotoxicity and non-liver AEs [in] patients who receive sotorasib after anti-PD-(L)1,” they add.

The study was published May 20 in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

Actionable Findings

“I consider the results to be highly credible and informative to my own practice,” said Jack West, MD, a thoracic medical oncologist at the City of Hope outside of Los Angeles and one of several lung cancer experts Medscape Medical News asked for comment.

The findings “may lead me to favor a trial of docetaxel as an intervening therapy for patients who have very recently discontinued immunotherapy, deferring sotorasib at least a few weeks and ideally several months,” West commented. “I think this is a particularly reasonable approach when we remember that sotorasib conferred no improvement in overall survival at all over docetaxel in the CodeBreaK 200 trial in KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC.”

Overall, the study “corroborates what we’ve seen in the limited first-line experience of sotorasib combined with immunotherapy and also echoes our experience of other targeted therapies, such as osimertinib administered in the weeks just after patients received immunotherapy, which is known to be associated with life-threatening pneumonitis,” he said.

Jared Weiss, MD, a thoracic medical oncologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said that given the long half-life of immune checkpoint inhibitors, “it is quite understandable that the toxicity challenges we previously saw with concurrent administration of immunotherapy and certain targeted therapies would be recapitulated in patients who had a relatively short interval between prior checkpoint inhibitor therapy and sotorasib.”

Even so, because of the aggressiveness of NSCLC, long treatment delays between immunotherapy and sotorasib therapy are “not a favored option.”

Like West, Weiss said docetaxel (with or without ramucirumab) is a sound intervening alternative.

Another option is to use adagrasib in the second line instead of sotorasib, Weiss suggested. It’s also a KRASG12C inhibitor but hasn’t so far been associated with severe hepatotoxicity, he said.

Hossein Borghaei, DO, a thoracic medical oncologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, agrees with his colleagues and thinks that what the French team found “is real.”

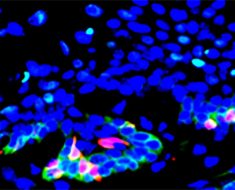

As the investigators suggest, “it might be that sotorasib leads to an inflammatory microenvironment that causes hepatotoxicity in the presence of a checkpoint inhibitor. In that case,” a lower dose of sotorasib might help reduce toxicity while remaining effective, Broghaei suggested.

Study Details

The French team was prompted to investigate the issue by a report of life-threatening hepatitis in a patient with NSCLC for whom sotorasib therapy was initiated 14 weeks after treatment with pembrolizumab, as well as by “the long story of adverse events…observed with sequential use of [immune checkpoint inhibitors] and targeted therapy.”

Like Weiss, they note that severe hepatotoxicity after anti-PD-L1 therapy has not, to date, been reported for other KRASG12C inhibitors.

Patients in the study were treated outside of clinical trials at 16 medical centers in France.

Half of the patients (24/48) who were treated immediately with an anti-PD-L1 after sotorasib therapy developed grade 3 or higher sotorasib-related adverse events, including 16 (33%) with severe sotorasib-related hepatotoxicity. Severe diarrhea and fatigue were also more frequent with sequential therapy.

Severe events typically occurred within 30 days of the last anti-PD-L1 infusion and to a lesser extent within 31 to 60 days.

In the control arm, the rate of severe sotorasib-related adverse events was 13% (7/54). Six patients (11%) experienced severe hepatotoxicity. There was one sotorasib-related death in the sequential therapy arm, which was due to toxic epidermal necrosis. No deaths occurred in the control group.

The two groups were balanced with respect to history of daily alcohol consumption and the presence of liver metastasis. More patients in the control arm had a history of hepatobiliary disease.

The study received no outside funding. Many of the authors report ties with pharmaceutical companies, including to Amgen, the maker of sotorasib, and Mirati Therapeutics, the maker of adagrasib. Details are listed in the original article. Weiss was an adagrasib investigator for Mirati. West is a regular contribiutor to Medscape and is an advisor for Amgen and Mirati as well as a speaker for Amgen. Borghaei reported extensive company ties. He has received research support, travel funding, and consulting fees from Amgen as well as consulting fees from Mirati.

J Thorac Oncol. Published online May 20, 2023. Abstract

M. Alexander Otto is a physician assistant with a master’s degree in medical science and a journalism degree from Newhouse. He is an award-winning medical journalist who worked for several major news outlets before joining Medscape. Alex is also an MIT Knight Science Journalism fellow. Email: [email protected]

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article